Prescription Tracking

Do You Count?

New research reveals what you

may have long suspected: You often don't get credit for the prescriptions you

write. Here's a look at the issues surrounding prescription tracking and

proactive measures you can take.

BY JENNIFER GOODWIN, CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

We have a problem in the ophthalmic industry, and it's time to face it head on. Historically, research firms that collect data for pharmaceutical companies have reported that optometrists prescribe only about 3% to 5% of all ophthalmic drugs -- with the rest being attributed to ophthalmologists, primary care physicians, pediatricians, allergists and other healthcare professionals. This seems quite unlikely to O.D.s. Even accepting the notion that M.D.s prescribe a higher volume of drugs than O.D.s, the fact that O.D.s outnumber M.D.s nearly 2 to 1 should offset this.

The interest over this prescription tracking issue ranges from a basic desire to get the facts straight to allowing optometry to participate fairly in the significant resources of the pharmaceutical industry -- which include detailing and sampling by pharmaceutical reps, educational sponsorship, research grants, advertising support in journals and participation at conferences.

|

|

|

|

ILLUSTRATION BY JOHN

BRUSZEWSKI |

|

A glaring problem

"I remember the shock I felt when a rep showed me the data," says Cliff Courtenay, O.D., of Valdosta, Ga. When looking at the numbers for a particular glaucoma drug, Dr. Courtenay found that his M.D. partner's numbers were twice that of his own.

"My partner was in the top 10% of ophthalmologists in this sample, which includes glaucoma specialists. We both see about 4 to 6 patients per day, and we have similar prescribing habits, so it's almost impossible for him to prescribe twice as much of that drug as I do.

"Obviously, there are some sources for error in this analysis, but the gross numbers are way out of line, which leads me to suspect that many of my prescriptions are attributed to my partner. This would also explain why he ranks so high in prescriptions for that drug compared to other doctors in our region."

Whether you can relate to Dr. Courtenay's account or not, you should think about measures you can take to combat the problem.

"Optometry is still evolving," says Dr. Courtenay. "To be sure that we receive the educational dollars and pharmaceutical rep attention that we need to thrive, it's paramount that O.D. prescription habits are accurately tracked."

Before searching for answers and defense tactics, let's take a closer look at the problem and what research indicates.

Pharmaceutical companies are leading the charge to obtain correct data. They want to know the truth about who prescribes their products, but it's not a simple task in a data collection system that's so deeply entrenched.

These companies rely on data about your prescribing habits that come from reporting firms, which buy the information from pharmacies. And this is where you're often left out. More often than not, that prescription you write is credited to someone else.

However, according to Juli K. Stone, vice president, National Accounts at National Data Corporation (NDCHealth), the company's independent validation re- search indicates that for an O.D. with his own prescription pad printed with his DEA number, data are nearly 100% accurate.

Recently, Alcon Laboratories commissioned a study with NDCHealth to provide a better understanding of what happens as prescriptions move from your practice to retail pharmacies and then to data collection agencies.

The study was supplemented by interviews with members of the American Optometric Association (AOA) to learn more about optometrists' concerns. According to doctors' own estimates in the Alcon/NDCHealth study, the average number of prescriptions they write ranges from two to three per day during regular times of the year to 10 to 15 per day during allergy season.

|

Number of Rxs per Winter Month per O.D. |

|

Artificial tears.....80 Source: AOA |

|

What other studies show

Other companies and organizations are also trying to get a better handle on the situation. Here's what they're doing and what their efforts have revealed:

AOA's new study. The AOA's just-released 2001 AOA Scope of Practice Survey analyzes the frequency of O.D. prescribing for various drug categories and reveals an even higher prescribing rate. Some of these data are shown in the table above in "Number of Rxs per Winter Month per O.D." (For extensive coverage of this survey, see the April 23 issue of AOA News.)

Allergan's study. Allergan worked on a separate study with SECO in March and April 2000. SECO's board gave Allergan a list of approximately 20 O.D.s. Allergan tracked the prescriptions of these O.D.s for two, 2-week periods and then for 1 month. It compared its findings to a tracking company's data and found that only 14% of prescriptions were tracked back to the correct optometrist.

"Although the results aren't statistically significant because of the small sample size, they're directionally consistent with other study data," says Jake VanderZanden, director of marketing and sales for Allergan.

From the O.D.'s viewpoint

The O.D.s interviewed for the Alcon study believed that they account for roughly 20% to 25% of all prescriptions written in the ophthalmic market.

In stark contrast, NDCHealth data show that only 4% to 5% of dispensed prescriptions in the ophthalmic market are attributed to optometrists.

About 26% of these prescriptions were written for anti-infective drugs, more than 47% were written for glaucoma treatments and about 18% were prescribed for anti-allergy products.

In the companies' eyes

The following pharmaceutical companies have their own views of the problem. Here's what some of their executives say about data they've received from IMS Health, another prescription tracking company.

Bruce Riddell, vice president of marketing at Santen Pharmaceuticals, explains that his company is studying existing data, and doing its own survey.

"O.D.s' prescriptions are underreported," he says, "But to what extent? I don't think anyone knows this quantitatively ."

Mr. Riddell continues, "All of us on the supply side of pharmacy want to know who our prescribers are and what products meet their needs."

|

|

What companies spend |

|

According to the pharmaceutical consulting firm Scott-Levin, pharmaceutical companies in the United States spent $5.3 billion in the first 11 months of last year, sending close to 100,000 sales reps into doctors' offices and hospitals, and $1 billion more holding marketing events for doctors. Some pharmaceutical executives think that optometrists don't bother to prescribe their products, so they focus their efforts -- and their dollars -- on other groups. According to IMS Health, one of the prescription tracking companies, face-to-face selling and physician-targeted advertising in the first 6 months of 2000 accounted for $2.7 billion, a 12% rise over 1999 first half figures. Pharmaceutical reps are a wealth of information and product sampling. They can inform your practice of the newest drugs on the market -- drugs that can make a difference to your patients. Reps spend time with you, leave information for you and your staff, and help stock valuable product samples. What if you're left out of the loop? If you're left out of this cycle, you can't compete with the ophthalmologists and family practitioners who'll be better informed than you. So why aren't those sales reps knocking on your door? According to Richard Edlow, O.D., chair, AOA Information and Data Committee, O.D.s surveyed in the 2001 AOA Scope of Practice survey said they saw an average of 2.8 drug reps over a 6-month period. According to Bobby Christensen, O.D., F.A.A.O., of Midwest City, Okla., "Pharmaceutical representatives are out there and are willing to do things with O.D.s, but sometimes O.D.s don't return calls. "What works well for reps is regional and county meetings. Group meetings of this sort cut down costs to pharmaceutical companies and allow them to give out more samples." His advice: "Organize meetings where pharmaceutical reps can talk about products and O.D.s can learn how to get samples. This betters the relationship between O.D.s and reps. Just call a company and ask them to send a representative for this purpose." |

Carl Spear, O.D., F.A.A.O., director of optometric marketing at Novartis Ophthalmics, expresses the same sentiments.

"Novartis is looking internally at some pilot-type beta testing programs to get a better look at the issue of underreporting.

"We have O.D.s call for samples or a visit from a sales rep, and we pull their prescribing information to find that they write few prescriptions. But when we talk to them, it becomes apparent that they're actually writing a good amount."

Dr. Spear describes his view of the problem: "Often, the problem is the pharmacist deciding that the prescription is from someone else. Our sales reps encourage O.D.s to work with pharmacists. That's where I think the numbers become different.

"The O.D.s who live in rural areas seem to have the highest prescribing numbers [better pharmacy relationships, more accurate tracking], whereas in urban areas, the pharmacist takes the prescription and an O.D. may not even get counted."

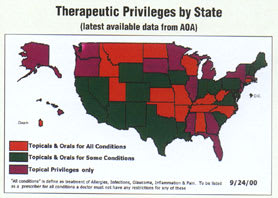

Leo Otero, product manager at Bausch & Lomb Pharmaceuticals, says, "O.D.s are underreported, but when an O.D. has TPA certification, some states have different levels of certification, so unless he's certified to the highest level, he can't be assured of getting proper credit.

"However, most companies are fairly confident that the M.D. quotient is accurately represented. M.D.s often get the credit over an O.D. when sharing a prescription pad," says Otero. He adds, "I think O.D.s are already an important group, but they'll gain more importance as this issue is clarified."

Aake VanderZanden from Allergan agrees.

"O.D.s have the best potential for increasing the credit they get for writing prescriptions," he says. "O.D.s are clearly the gatekeepers for treating most eye conditions."

"That said, Allergan knows that O.D. prescription tracking is a problem," continues VanderZanden. "That's why we've changed the deployment of our sales force to cover a broader base of O.D.s."

The data capture process

When filling a prescription, the pharmacist takes some vital statistics into his database. These include the prescribing physician's DEA number, assigned by the Drug Enforcement Agency to track controlled substances. As each state developed its optometric therapeutic drug act, some authorized optometrists to apply for DEA numbers, some authorized DEA-like numbers and some didn't authorize any.

According to the just released scope-of-practice survey by the AOA, 55% of practicing O.D.s with therapeutic privileges don't have DEA numbers.

Years ago, a physician's DEA number became a convenient way to track and credit prescriptions. Today, however, prescribing authority is shared by ad- vanced practice nurses in 48 states, physician assistants in 45 states and certified nurse midwives in 33 states. Homeopaths have such authority in three states and pharmacists in nine states. Very few of these practitioners hold DEA numbers.

Yet, pharmacies continue to track prescriptions through the same methods because it's legally required by many states.

"Our policy is to track set fields of information for all prescriptions," says Carole Hively, corporate spokeswoman at Walgreen's Pharmacy.

"These fields include the doctor's zip code, DEA number and what he prescribed. We then sell his prescribing information to companies that eventually send it to pharmaceutical companies."

This practice happens in most pharmacies. NDCHealth receives prescription data from more than 60% of all retail pharmacies in the United States. That's more than 36,000 pharmacies.

These pharmacies provide NDCHealth with more than 74% of all prescriptions dispensed in retail outlets in the United States. NDCHealth attempts to match a prescription to a practitioner primarily, but not only, by tracking DEA numbers.

Prescribing optometrists who don't have DEA numbers will most likely not be matched accurately. To fill in the blank, a pharmacist may decide to use your patient's primary care physician's DEA number, or even a pre-approved DEA number by a managed care organization.

In either case, you're no longer associated with that prescription. You become lost in the database. In fact, in the Alcon study, two of eight practicing O.D.s interviewed weren't found in the NDCHealth database at all. Six optometrists interviewed for the Alcon study agreed that the NDCHealth data represented only 66% to 75% of the actual volume they prescribed.

|

Are O.D.s Guilty of Oversampling? |

|

By Neil B. Gailmard, O.D., M.B.A., F.A.A.O., Munster, Ind. I was at a meeting recently with executives from several of the major ophthalmic pharmaceutical companies, and someone brought up the topic of tracking prescriptions. As we discussed the frequency of sales reps calling on optometric practices and the practice of leaving drug samples, one of the executives mentioned that optometrists are known to "oversample their patients." I asked executives from all the companies if they agreed with this premise -- and it was unanimous. They perceived it was a well-known fact. And it's not just based on the numbers of samples distributed compared to the number of prescriptions written -- but also on the general perception of their sales reps. O.D.s ask for samples more often than M.D.s, and they go through them faster. Some of the reasons cited for the practice are interesting. For example:

No matter what the reason, if it's true that we do sample more freely (and I suspect it may be), we should take active steps to change the practice. It's bad for our profession and the industry because such misuse drives up costs and results in giving us a poor image. One pharmaceutical executive summed it up well. He said that the major difference between O.D.s and M.D.s is that M.D.s give a sample and a written prescription for a drug, whereas O.D.s just give the sample. Not writing the prescription results in an increased sample-to-prescription ratio, and it could lead to noncompliance in patient care. |

|

Filling and billing

"Pharmacies need to be paid for the prescriptions they dispense, and some managed care organizations will only recognize a DEA number, "says Dr. Williamson, of Cape Coral, Fla.

"In Florida, we don't have DEA numbers, but we do have prescriber numbers. Instead of calling us first, some pharmacies use their own DEA number or credit the patient's primary care physician number to get around the managed care organization's rules. We lose out."

Chris Williamson, O.D., also a participant and in practice with his father in Cape Coral, says, "I remember an incident where the pharmacist wasn't aware that O.D.s in Florida have the authority to prescribe medications.

"The patient was refused the medication. We had to call the pharmacist and educate him about the new laws regarding optometrists' prescribing authority in our state."

Imagine a pharmacist saying this to one of your patients:

"Mary, because you were treated by an optometrist, your insurance won't cover the cost of your prescription eye drops.

"You'll have to pay for it yourself. You know, if you had seen an ophthalmologist, it would've been covered."

This actually happened to one of Dr. Neil Gailmard's patients.

"Actually," Dr. Gailmard explains, "the insurance company didn't really discriminate against O.D.s in this case, but their computerized billing system required a DEA number, which Indiana optometrists can't obtain.

A common understanding

"Pharmacists have told my patients that I didn't have the proper license number so my prescription couldn't be filled. They couldn't process the prescription without a DEA number for the computer program, which is used for third party billing."

Dr. Gailmard explains that in cases such as this, he gets a phone call, asking for his DEA number. He tells the pharmacist that the drug he prescribed isn't a controlled substance and doesn't require a DEA number. He says that he's certified to prescribe therapeutic drugs in the state. The pharmacist agrees that a DEA number isn't required for the drug class, but rather for identification.

"Cases like this undermine the doctor-patient relationship, and can't be tolerated," he says.

"We have a great drug law in Indiana, which includes glaucoma and oral medications, but we aren't authorized to obtain DEA numbers. State officials say we don't need one because we don't prescribe controlled substances, but they miss the point.

"Most pharmacies have found a way around the problem so problems with filling and billing happen only rarely now. A large national chain has agreed to insert its own store DEA number in the field. It lets our patients use their insurance, but I'm sure Indiana optometrists aren't being tracked properly because of this.

"I even had a mock number printed on our prescription pads followed by the statement, 'For billing purposes only.' This has worked for many pharmacies, but it doesn't help the inaccuracies of prescriber tracking."

The barriers to completely accurate tracking are varied. They don't all pertain to an optometrist's DEA number, but they do include the following issues.

Group practice offers many advantages, but when it comes to tracking prescriptions correctly, too many names on a prescription pad can be a recipe for trouble. Several factors contribute to confusion when a pharmacist is trying to fill a prescription.

If you don't write clearly, with a legible signature, the pharmacists may credit a different name on the pad.

Some pharmacists revealed that they're instructed to assign a prescription to the doctor whose name most closely resembles the signature. If the pharmacist is very busy, he has even less time to search for the accurate prescriber. One pharmacist speculated that a physician's signature on a prescription is unreadable 20% to 30% of the time.

If the O.D. doesn't have a DEA number, but the M.D. listed as part of the same group practice does, the pharmacist may assume it doesn't matter if she gives credit to the M.D. instead.

Approximately 40% of prescriptions written are never filled by a patient. Fewer are refilled.

"I was flabbergasted to learn that a third of my patients never fill the prescriptions I give them," says Stuart Thomas, O.D., of Athens, Ga., a participant in the Alcon/NDCHealth study.

"Patients may not understand the importance of taking their prescriptions. We need to spend more time educating them about the importance of compliance."

Pharmacies nationwide are experiencing a staff shortage.

"We found there to be about 3,800 pharmacist vacancies across the country, which is about a 12% shortage," says Phil Schneider, managing director of public affairs for the National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Other sources estimate the shortage to be 20% to 25%.

In addition, the Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association revealed that 92% of responding pharmacists are "very often or often interrupted while filling a prescription." One can see how prescriptions are credited to the wrong practitioner.

The pharmacists interviewed in the Alcon study indicated that although they recognize misidentification as a problem, they don't consider it to be critical.

The survey revealed that where a DEA number is required and the prescribing optometrist doesn't have one, the pharmacist will either use the patient's primary care physician's DEA number, or a pre-determined number.

Suggestions for improvement

Perhaps the greatest challenge to accurately tracking O.D. prescription habits is a lack of DEA numbers for O.D.s in all states. Insurance companies and managed care organizations require most pharmacies to cite a DEA for reimbursement. To fulfill this, pharmacists will most likely continue to substitute a primary care physician or MCO-authorized number if the prescribing O.D. doesn't have a DEA number.

The DEA never intended its numbers to be used in this manner. The numbers are designed to track controlled substances. One recommendation from Alcon/ NDC Health's study was to ask the DEA to issue a special subset of numbers for O.D.s to track all drugs for which they write prescriptions.

"DEA numbers for O.D.s is a critical issue," says Dr. Thomas. "SECO is looking at it, and so is the AOA. Hopefully, we'll come up with viable solutions."

|

|

|

|

|

Here are some other tips to consider if you think you're not being accurately counted.

If you practice in a state that allows you to apply for a DEA number, do so and make sure it's on all of your prescription pads.

Get individual prescription pads for each O.D. in your practice to ensure accurate credit.

Dr. Christensen says that if you share a pad with other doctors, often the doctor listed on top gets counted as writing that prescription. Also, an M.D. listed along with other names is more likely to get the credit.

Ask your patient to bring his medication to the follow-up visit. Check whether the correct caregiver is credited for it.

Get to know the pharmacists in your area. Many are unaware of the long-term impact of a misrepresented DEA number.

Where do you go from here?

There's no question about it -- you're not always getting proper credit for writing prescriptions. So, what's next?

Resolving this problem needs to be a cooperative effort between optometrists, pharmaceutical companies and tracking companies. As the AOA and others bring this problem to the forefront, We'll likely have more solutions at our fingertips.