CLINICAL CHALLENGES

Things that Go Bump in the Night

20/20 vision doesn't always mean a normal examination.

Usually, a thorough slit lamp exam and stereoscopic viewing can identify the problem and the cause of a patient's eye complaint. But at times the exam is essentially normal, and tests give us no additional clues -- though a problem does exist. Then we have to rely on our ears as much as our eyes to determine what's wrong with our patient.

The problem

Mr. B. came to my office about 1 year ago. He said that he was "seeing great" but worried that he was missing things to his left, causing him to bump into objects, especially at night. Mr. B. stated that he wasn't dizzy and didn't feel that he was losing his balance.

He'd first noticed the problem 9 months earlier, but because he could still see well, he'd put off visiting any doctor until now.

Mr. B. was a 63-year-old construction superintendent who took no medication. He'd last seen an eye doctor 40 years earlier, and wore only reading glasses when needed. He hadn't seen a medical doctor for years.

On further questioning, he denied having paresthesia, dizziness or headaches, but men-tioned that his wife noticed that he turned his whole head to the left when he was driving.

|

|

|

|

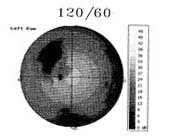

Left homonymous hemianopsia. Note how the defect respects the vertical

meridian. |

|

Examining Mr. B.

I measured Mr. B.'s visual acuity as 20/20 OU without spectacles. Pupils measured 6 mm OU and were equally round and reactive with no afferent pupil defect. Extraocular muscles showed no restriction.

In confrontation visual fields, Mr. B. consistently showed constriction in his left field of vision OU. It appeared to be denser above than below the horizontal. The rest of his examination was essentially normal. He had a mildly hyperopic refraction. The slit lamp exam showed no disease, and the dilated fundus exam revealed no disk swelling, no retinal hemorrhages, no drusen or macular changes and no retinal holes or tears. I saw a faint spontaneous venous pulse OU. Goldmann tonometry results were 19 mm Hg OD, 21 mm Hg OS, but his blood pressure (BP) was 195 mm Hg over 95 mm Hg.

Mr. B. was exhibiting a left homonymous hemianopsia with an otherwise normal exam. I wanted to confirm the visual field defect. A 60-degree automated threshold field test found a significant left homonymous hemianopsia. The defect was much denser above than below, and it respected the vertical midline well (page 98).

Neuro-anatomy 101

In the differential diagnosis of a homonymous hemianopsia, the potential etiologies are limited. Visual field defects themselves are localized because of the manner in which the nerve fibers in the visual pathway travel.

At the optic chiasm there's a decussation of the nerve fibers, but only the nasal fibers of each eye cross over. In the right eye, the nerve fibers responsible for the temporal retina don't cross to the left side of the brain; they synapse and terminate at the right visual cortex. The fibers responsible for the right nasal retina end in the left visual cortex, crossing at the optic chiasm.

|

|

|

|

Visual field of same patient (Mr. B.) performed 5/30/01. Note how the defect is smaller but still dense and respecting the vertical

meridian. |

This same pattern holds true for the left eye. A lesion that produces a left homonymous hemianopsia must occur posterior to the optic chiasm and must impinge the temporal fibers of the right eye (yielding a relative nasal scotoma OD) and the nasal fibers of the left eye (producing a temporal defect OS). Thus you can localize the lesion to the posterior fossa.

A field defect that's denser above than below suggests a temporal lobe lesion, but the fact that this defect was congruous (similar in both eyes) indicated an occipital lobe lesion.

Narrowing it down

The potential causes of Mr. B.'s visual field defect were:

- a lesion of the temporal, parietal or occipital lobe

- a lesion in the lateral geniculate body or optic tract just post-chiasmally

- head trauma

- tumor, stroke or aneurysm.

Migraine syndrome could produce a hemianopsia, but it would generally be transient.

Mr. B. denied head trauma. Aneurysms usually don't produce a quiet hemianopsia; they almost always cause headaches. Mr. B. denied having head-aches upon repeated questioning, so an aneurysm was unlikely.

I suspected a tumor of the temporal lobe, although a cerebrovascular accident (CVA or stroke) was possible. Mr. B. exhibited no signs of a CVA except elevated BP. I needed to rule out a brain tumor first, so I ordered a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan with gadolinium contrast dye, dir- ecting the radiologist to look for a mass lesion of the posterior chiasm.

A positive I.D.

The MRI showed no mass lesion, but the radiologist identified a 3-cm by 1.5-cm area of decreased signal intensity in the right occipital lobe. He felt it related to a no longer acute CVA. Apparently, Mr. B. had suffered a stroke 9 months before, and it left him with no signs other than the field defect.

Mr. B. came to my office to discuss the findings. I remeasured his BP; it was 208 mm Hg over 142 mm Hg. I told him about his stroke and explained that his extremely high BP had probably caused it. He was at risk for another, more serious, stroke, so I arranged for an internist to see him that afternoon.

The internist placed him on oral clopidogrel (Plavix) for hypercholesterolemia and a systemic beta blocker (atenolol [Tenormin]) to lower his BP.

Mr. B. today

Mr. B. has remained symptom-free for 1 year. His BP is well controlled and his vision remains 20/20 OU. He says that his "not-seeing area" has shrunk. A repeat visual field corroborated this, showing a much smaller, but still dense, left homonymous hemianopsia (page 101). He's probably developed collateral circulation in the occipital lobe to improve blood flow to the injured area. But it's unlikely that any more improvement will occur.

Mr. B.'s condition is stable. He understands how lucky he was and that he must continue to control his BP and cholesterol level. I'll see him annually unless he feels the need to see me sooner.

Contributing Editor Eric Schmidt, O.D., is director of the Bladen Eye Center in Elizabethtown, N.C. E-mail him at KENZIEKATE@aol.com.

|

CLINICAL PEARLS |

|