Malpractice

Management

Avoidable Disaster?

A routine cataract extraction leads two practitioners on the road to litigation.

BY JERRY SHERMAN, O.D, F.A.A.O.

BY JERRY SHERMAN, O.D, F.A.A.O.

Modern cataract surgery has become one of the most common, successful and safe surgical procedures in the United States. Although an estimated 95% of patients do well, perhaps 5% of the million or so procedures each year have unfortunate outcomes and some of these failures lead to litigation.

Read on and see whether you believe that the optometrist could have prevented the poor result in this case.

Reviewing the case

A 76-year-old woman presented to her primary care optometrist to check on the progression of a previously diagnosed cataract in her left eye. She complained of increasing difficulty driving and reading and was especially troubled by glare from headlights while driving at night.

Her eye history revealed amblyopia in her right eye (diagnosed as a child), myopic degeneration in her right eye and a poor outcome following cataract surgery in the right eye nearly a decade earlier.

The optometrist refracted the patient, but couldn't improve on the previous prescription, which yielded 20/400 visual acuity (VA) OD and 40/40- VA OS. Externals revealed an anterior chamber implant OD with corneal edema. Slit lamp exam of the left revealed a 2++ nuclear cataract that appeared to have increased in density from previously recorded evaluations.

Bringing in help

Because of the myopic degeneration, the optometrist had previously referred the patient to a retinal specialist who agreed with the optometrist that untreatable myopic degeneration was partially responsible for the reduced vision in the patient's right eye.

Based on the patient's increased complaints, reduction in the best correctable VA OS and the slit lamp finding of a progressing nuclear cataract, the optometrist this time referred the patient to a cataract surgeon for consultation.

The referral was to a highly regarded ophthalmologist who was performing nearly 2,000 extractions each year. He spent one day each month in the O.D.'s office examining referred patients, mostly those with cataracts. (The M.D. paid $500 rent per session to the O.D. for use of his facility, personnel and equipment.)

The M.D. told the patient that glasses could no longer improve her vision and that cataract removal was the next logical consideration.

|

|

|

|

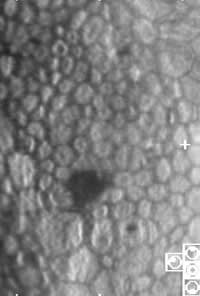

Healthy endothelial cells (cell count about 2,600 cell/mm2). |

|

|

|

|

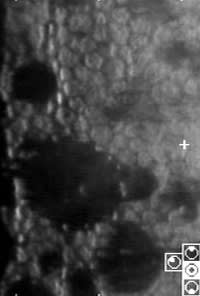

Mildly abnormal endothelial cells (cell count about 1,500 cell/mm2). |

|

|

|

|

Moderately abnormal endothelial cells (cell count about 1,000 cell/mm2). |

Proceeding

The surgeon's findings were essentially the same as the referring optometrist's. He did note that the pseudo-phakic bullous keratopathy in the right eye was likely caused by the anterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL), a type that the manufacturer withdrew from the market because of FDA objections. He also noted some corneal guttata with Fuchs' dystrophy in the left eye but felt that he could do it with phako emulsification.

The surgeon reviewed the risks benefits of cataract extraction with the patient. She agreed to the surgery and signed a typical informed consent document.

Bad news for everyone

The cataract extraction via phako emulsification went quite well, but on the first post-op visit, the optometrist couldn't improve VA in the OS better than 20/200. He noted corneal edema and corneal folds. He replaced the routine treatment of dexamethasone 0.1%/tobramycin 0.3% q.i.d. with prednisolone acetate 1.0% every three hours. When the surgeon saw the patient in the post-op period he told her that because of the previously diagnosed Fuchs' dystrophy, it may take six weeks to six months for the corneal edema to clear.

The corneal edema never did clear and the patient's VA never improved. She sued both the optometrist and the ophthalmologist because of the negative outcome.

Meeting the standard

Clear cornea phako emulsification is generally considered the standard cataract extraction procedure in the new millennium. Essentially all good surgeons expect (but do not guarantee) excellent outcomes.

Corneal guttata and Fuchs' dystrophy occasionally lead to corneal decompensation after phako emulsification. As a general guideline, if one eye develops corneal decompensation after phako, then the surgeon should use traditional extra capsular cataract extraction (ECCE) on the second eye.

Taking the stand

In his deposition, the M.D. testified that not a single patient of his with Fuchs' ever decompensated and required a corneal transplant. This patient was the first. The O.D. testified that he only referred the patient for a surgical consultation and that he never guaranteed her a favorable outcome.

As far as culpability is concerned, I formally opined as a defense expert that the O.D. clearly met the existing standard of care. The referral for a cataract consultation was clearly indicated and appropriate.

Above & beyond

Although the patient's right eye developed corneal edema, it was likely caused by the anterior chamber IOL that was later shown by the FDA to be responsible for corneal decompensation. Could the O.D. or the M.D. have performed a procedure that may have predicted the negative outcome in the left eye?

The answer is yes. Using the Konan cell check system, either practitioner could have obtained the corneal endothelium cell count non-invasively within one minute or so. Patients who have cell counts above 2,000 cells per square millimeter have a small risk of decompensation while patients who have cell counts below 1,000 are at a much greater risk.

Although measuring the density of endothelial cells before cataract extraction isn't the present standard of care, routine use of this technology will likely identify the patients at greatest risk. These identified patients could then be given the choice of phako or ECCE.

How it ended

The patient dropped all charges against the O.D., but the M.D. and his insurance carrier decided to settle the litigation before a jury trial took place for a sum between $100,000 and $200,000. It's unclear whether the patient has decided to go through with a corneal transplant in the left eye.

Dr. Sherman practices at the Eye Institute and Laser Center in Manhattan and is a distinguished teaching professor at the SUNY College of Optometry. To protect the anonymity of the individuals involved in this case, we have not used their real names.