CLINICAL CHALLENGES

High Tech for Low Tension

Normal tension glaucoma is hard to catch early on, but new imaging technology makes it easier.

![]() By Eric Schmidt,

O.D.

By Eric Schmidt,

O.D.

Eyecare professionals traditionally make the diagnosis of low or normal tension glaucoma (NTG) later in the disease process. Because of its insidious nature and the normal intraocular pressures (IOP) that characterize the disease, it's often difficult to make an early diagnosis. But as the following case illustrates, advancements in imaging technologies have made earlier diagnosing of NTG easier.

Inheriting a mystery

A capable primary care optometrist sent a referral note to me in which he described the case of Mr. B, a 57-year-old African-American male, whom he'd been following as a glaucoma suspect for two years.

In that time period, the referring optometrist measured Mr. B's IOPs eight times and not once was it more than 20 mmHg. It did, however, range from 14 mmHg to 20 mmHg. This doctor also performed two visual fields, both of which were normal. He also told me that gonioscopy was open OU.

What befuddled this O.D. was the appearance of Mr. B's optic nerves. They were large with a great deal of cupping. He graded the cup-to-disc ratio (C/D) as .9/.8 OD and .8/.7 OS. In his words, they "screamed of glaucoma."

Despite the appearance of the optic nerve head (ONH), the referring O.D. was reluctant to initiate therapy for NTG because of Mr. B's consistently normal IOP and the lack of any visual field defects.

Not enough to go on

The issue of whether or not to treat a patient such as Mr. B is difficult -- and eye doctors everywhere have wrestled with it for a long time. You obviously don't want to prescribe medication for a patient when you're not sure whether he has glau-coma. But you also certainly don't want to let a potentially blinding disease progress unchecked. For cases similar to this one, you have to glean as much information as you can from the patient's history, his examination and any other objective findings you can gather.

Performing initial tests

Mr. B presented to me with no ocular complaints other than being "worried about this glaucoma." He told me that he was not aware of any family history of glaucoma. He was currently taking valsartan to control hypertension and ranitidine HCl as needed for heartburn.

Mr. B's visual acuity (VA) with his spectacles was 20/20 in each eye. He was mildly hyperopic and also presbyopic. Extraocular muscles, pupils and confrontation visual fields were all normal. His anterior segments were free of pathology and his IOP measured 16 mmHg OU at 10:30a.m.

I placed a Sussman gonioscopy lens on both of his eyes to view the anterior chamber angle. I judged the angle as Grade 3 360 degrees OD and Grade 4 in 3 quadrants and Grade 3 nasally OS. There were mild iris processes throughout the angles OU. Using a pachymeter, I measured his corneas and found them somewhat thin at 510 µm OD and 505 µm OS.

Reviewing the findings

As I was waiting for Mr. B's pupils to dilate, I reviewed his visual fields that the referring O.D. sent to me. Both tests were reliable, making the results valid. Both showed no mean loss of sensitivity or any pattern defects in either eye. They were indeed normal visual fields.

Conversely, his ONHs didn't look normal. The discs were about average in size, but there was a great deal of cupping OU. I examined the ONH with a 78.00D lens and estimated the cupping in the OD at .95 temporally, .85 nasally, .9 superiorly and .85 inferiorly.

The OS ONH was similar with cupping of .95 temporally, .8 nasally and .85 both superior and inferiorly. Both ONHs had thin temporal rims and large alpha and beta zones around their circumference (See images above).

It was also significant to me that I could easily see laminar dots in the base of the ONH OU. And when I looked at the slope of the neuroretinal rim into the base of the nerve I noticed that it was rather gradual and shallow, which some experts say is a characteristic of NTG.

One more bit of data

I've told many optometry students and doctors that if a case looks, smells and tastes like glaucoma then it probably is glaucoma. In this case, I agree with the referring doctor that Mr. B's ONH "screamed" glaucoma, but given his normal IOPs and normal visual fields, it would be nice to have some additional information regarding the health and function of his ONH.

Fortunately, we now have instrumentation that provides us with exquisite objective views of the ONHs, peripapillary regions and macula. In this case a retinal thickness analyzer gave me the information I needed to decide that treatment was warranted. The retinal thickness analyzer showed mildly attenuated temporal, superior, nasal, inferior, temporal (TSNIT) curves at the ONH with one area of significant focal loss superotemporally in each eye.

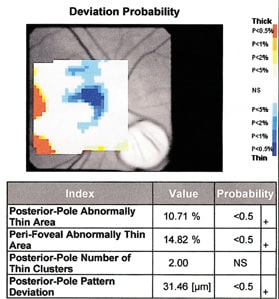

But more significantly, the retinal thickness analyzer revealed large areas of significant retinal thinning at the posterior pole just above and below fixation OU (See images below). These results are indicative of a great deal of retinal ganglion cell loss at the NFL. Because of its proximity to fixation and the depth of this defect, Mr. B is at great risk for not only a double arcuate scotoma to develop rather abruptly, but also a loss of VA.

Getting some treatment tips

On the basis of the results of the retinal thickness analyzer and the appearance of Mr. B's ONH, I felt that he did have NTG OU and would benefit from IOP lowering treatment.

The Collaborative Normal Tension Glaucoma Study (CNTGS) provides us with some guidelines for treating this disease. One conclusion that the CNTGS came to was that once a physician makes the diagnosis of NTG aggressive therapy is warranted to quell progression of the disease. The study suggests that a 30% reduction in IOP is necessary for mild cases of NTG (based on visual field results).

For moderate cases of NTG, the study suggests a 40% reduction in IOP. The CNTGS also shows that you should base the target IOP drop from the patient's highest untreated IOP. Another tenet of treating NTG is that any drop you prescribe shouldn't negatively impact ocular blood flow.

Mr. B had mild NTG so our target IOP is a 30% drop from his highest IOP, which was 19 mmHg OD and 20 mmHg OS, making our target IOP between 13 mmHg and 14 mm OU.

|

|

|

|

Thickness deviation probability maps showing clinically significant thinning of the superior arcuate bundle OD (right image) and superior inferior arcuate bundle OS (left image). |

|

Forging ahead

I prescribed bimatoprost 0.03% OU q.h.s. in hopes of achieving this. After three months, Mr. B's IOPs never dropped below 15 mmHg, so I prescribed travoprost 0.004% OU q.h.s. The travoprost produced similar results. I subsequently prescribed brimonidine tartrate 0.15% OU b.i.d., which also failed to lower his IOP to the target level.

I eventually ended up placing Mr. B on a regimen of bimatoprost OU q.h.s. and brimonidine tartrate OU b.i.d. When I discharged him back to his original doctor, Mr. B's IOPs measured 10 mmHg OD and 11 mmHg OS. According to the correspondence I receive from the other doctor, Mr. B's IOPs and ONHs are staying stable on this combined therapy.

Contributing Editor Eric Schmidt, O.D., is director of the Bladen Eye Center in Elizabethtown, N.C. E-mail him at kenziekate@aol.

|

CLINICAL PEARLS |

|