Gaining Greater Efficiency and Profitability Through the Use of Automated Refraction Systems

Automation will improve efficiency and profitability. Here's why you should begin planning now and some tips for a smooth transition.

By Louis J. Catania, O.D., F.A.A.O., Mary Rosenbaum, O.D., and Monica Brown, O.D.

Integrated electronic automation can be loosely defined as the automated coordination of clinical and business procedures, data and functions with or without the use of paper records (hard copy) through specialized electronic hardware and software (instruments and systems). Reasons and rationale for such a process in optometric practice become more obvious with each passing month. It won't be long before such integration will be a necessity rather than an option for practitioners.

Before mandatory regulations and their financial implications arrive, it would be wise for the optometrists (a.k.a. "practice business managers") to understand the values, benefits and implications of an integrated electronic automated office. Questions related to this practical issue range from personal comfort to clinical quality of care to technology issues and even to intermediate and long-term professional competition.

This article will discuss the current and future practical issues, technologies, financial implications and challenges in developing an integrated electronic automated practice. We'll outline the compelling, practical reasons for such changes from traditional practice structures. We'll also suggest immediate, intermediate and long-range plans of action that practitioners may consider using for various types of practices.

Reasons and Rationale

Healthcare practices of all kinds are service businesses. The nature of the services provided varies from one profession to another as do the routine procedures, technologies and reimbursement mechanisms utilized. There are also common denominators like clinical recordkeeping, data transcription and transfer, bookkeeping, billing and coding, appointment scheduling and insurance authorization. Even subtle things like practitioner boredom and burnout are common to most healthcare practices.

Optometry practices face the common denominators mentioned above, as well as some characteristics that are unique to vision care. A quick review of some unique and common practical issues in optometric practice provides a good set of reasons and rationale for moving forward with integrated electronic automation.

Repetitive Motion Disorders

One of the most common procedures an eyecare practitioner performs is the refraction. Depending on the nature and size of your practice, it can represent anything from 20% to 90% of a typical work day. This common procedure includes some rather awkward postures, positioning and movements, which the eyecare practitioner will repeat hundreds of times per week (Figure 1).

Repetitive motion disorders (RMDs) are a family of conditions that result from repeated motions performed in the course of normal work or daily activities. They generally present no visible signs of injury, but can cause varying degrees of pain, tingling, swelling, loss of flexibility and strength.

Figure 1. Performing manual phoropter refractions repeatedly can cause physical discomfort due to the poor ergonomics of the technique and certain types of equipment.

Figure 2. Performing a refraction with an electronic phoropter allows the practitioner to sit more comfortably during the procedure.

If you're a busy optometrist, ask yourself the following questions:

■ Does your dominant hand go to sleep?

■ Has one shoulder become painful on movement?

■ Has your neck been stiff?

■ Have you suffered sacroiliac joint pain?

■ Have you experienced light-headedness?

■ Do you have headaches?

Certainly, these signs and symptoms may not be related to RMD in every case, but if you do a lot of routine refractions, the potential association can't be denied.

Refraction is perhaps the single worst ergonomic clinical procedure in eye care and most optometrists do a lot of it. Automated refracting systems, as part of an integrated electronic automated practice, provide an alternative and potential relief from the risk of RMD (Figures 2 and 3).

Pending Reimbursement Regulations

The integrated electronic automated practice increasingly is being viewed as an essential component in reducing transcription and transfer errors in practice. And beyond data transfer, electronic integration also improves the efficiencies of appointment scheduling, insurance authorization, medication and dispensing information, accounts receivable, patient recall and more. These improved efficiencies in the integrated practice also improve documentation, support appropriate billing and coding, and meet HIPAA and other regulatory requirements. All of this effectively improves the quality of care and reduces the cost of eye care and health care in general.

Figure 3. Various electronic phoropters are available, and all offer increased comfort and ease of use compared to manual phoropters.

In clinical studies and practice models, cost/benefit ratios and improved quality of care through integrated electronic automation are demonstrating improved communications between professionals, more accurate clinical decision-making and more timely diagnosis and management. Because of this, third party payers, including the federal government, have decided that the integrated electronic automated practice is key to improving the quality of care and controlling healthcare costs. These decision-makers have set timelines for practices to convert their record-keeping, documentation and billing practices to electronic ways and means.1 Reimbursement and qualification incentives will begin in 2010, with electronic automation becoming mandatory by 2014.

Examples of incentives to be implemented in 2010 include positive differentials in reimbursements for billings submitted electronically. Practices using electronic medical records also will be credentialed as "Best in Class" for a given profession, a distinction that can serve only to help increase your patient intake. By 2014, according to the current administration's initiatives, it's simple. If your practice isn't electronically integrated, you don't get paid!

Technology Considerations

Electronic Medical Record. The heart of an integrated electronic automated practice is the electronic medical record or EMR. It's almost self-explanatory as being a coordinated, digital record for all patient information (clinical and business) in a practice. The EMR is a mandatory component of a functioning integrated electronic automated practice and vice versa. Electronic equipment and instrumentation collect data, transcribe it and transfer it directly to the EMR. The EMR can deliver reports digitally or through hard copy. Table 1 is a limited list of some of the functions and capabilities of a standard EMR system.

| TABLE 1 Functions and capabilities of a standard EMR system: ■ Appointment-making ■ Completion of patient forms (history, billing information, etc.) through a Web site with electronic transfer in advance of appointment ■ Checking in process ■ Billing authorization ■ Collection of all clinical data ■ Data transfer ■ Data transcription ■ Accounts receivable ■ Insurance authorization ■ Patient information search (appointment record, credit record, employment information) ■ Medication and dispensing information ■ File same-day electronic claims ■ Generate custom correspondence, reports, referral letters, etc. for immediate transfer ■ Laboratory orders, frame inventory, tracking orders ■ Patient recall. |

| Refraction is perhaps the single worst ergonomic clinical procedure in eye care and most optometrists do a lot of it. |

There's an increasing national priority to digitize health care. Thus, the development of software solutions, instruments, hardware technologies, economics and ergonomics have begun to intersect. The evolution of the paperless practice already is a reality using existing off-the-shelf products and services. And electronic automated instrumentation is at a level of sophistication that translates into a high level of eye care that wasn't even dreamt of as little as 10 years ago.

| TABLE 2 Limited list of electronic automated eyecare instrumentation: ■ Automated digital autorefractors (e.g., M3 by Marco Ophthalmics) ■ Automated visual field instruments (e.g., FDT by Humphrey) ■ Computerized automated phoropters (e.g., Epic and TRS by Marco) ■ Coherent ocular tomography (e.g., RTS by Marco) ■ Digital imaging systems (e.g., Haag-Streit EyeCap System) ■ Pachymetry (e.g., Sonomed AB-5500+ E-Z Scan) ■ Retinal cameras (e.g., Topcon TRC) ■ Scheimpflug imaging (e.g., Pentacam by Oculus) ■ Topographers (e.g., Orbscan by B&L) ■ Wavefront aberrometers (e.g., 3D Wave by Marco) |

Electronic Automated Instrumentation. There's electronic automated instrumentation for virtually every diagnostic area in eye care. Moreover, it continues to improve in its versatility, scope and accuracy. Many clinical diagnoses today couldn't have been made 5 years ago. Most compelling is that most of these exciting technologies continue to become more accurate, smaller, easier to use, more efficient and more affordable.

Perhaps of greatest practical value in the explosion of electronic automated instrumentation is the fact that virtually all of it can be integrated with almost any EMR system on the market. Simply stated, if an instrument plugs in, it should be able to integrate with an EMR system. If it can't, don't buy it!

It would take numerous textbooks (being published regularly now) to cover the full range of electronic automated eyecare instrumentation available. But a short list (Table 2) of the more prominent ones in optometric care gives a thumbnail picture of the ever-increasing choices.

Again, using the routine refraction as one example, let's consider how we can enhance clinical quality of care through the integration of electronic automated instruments.

By using the 3D Wave by Marco and the TRS or Epic electronic automated phoropter, you can perform a custom wavefront refraction using the aberrometer's software to analyze the effects of higher order aberrations (HOAs) on lower order photopic and scotopic refractions. This analysis is transmitted to the electronic phoropter in seconds for the patient to select his preferred prescription for daytime or nighttime use or separate prescriptions for each condition (if HOAs are producing significant enough prescription differentials). Such accuracy and efficient analysis weren't possible before the new electronic automated instruments entered the scene.

The benefits of automated electronic instrumentation integrated with the EMR are numerous and varied according to their specific diagnostic purposes. A list of the benefits of integration are enumerated in Table 3.

Financial Implications

Some practices delegate and some don't, guided either by state regulations or personal preference. Though more effective with delegation, an integrated electronic automated practice offers greater efficiency, cost effectiveness and quality of care with or without delegation.

Improved efficiencies improve the quality of care by allowing practitioners to spend more time with their patients in an integrated automated practice. That added time has strong potential to improve the quality of care (e.g., better patient education and counseling), as well as increased potential for patient satisfaction and practice growth. That time also can be used for increased revenue generation.

Included in the "patient education and counseling" mentioned above, some automated practices have introduced the concept of a lens center in the exam room (a concept developed by Lance Mallot, O.D., and Jerry Lamberson, O.D., of New Castle, Ind.). The exam room lens center allows the practitioner to discuss and provide audiovisual demonstrations of new lens technologies that could benefit the patient. Because the doctor provides this information as part of his professional care, this can result in substantial benefits to the patient and to the practice's gross revenue.

All of the potential benefits realized in the integrated electronic automated practice are positive considerations for change, but there are, of course, some negatives and some challenges to be considered.

| TABLE 3 Benefits of integrated electronic automated instrumentation and EMR: ■ Computer accuracy and reliability ■ More quality time to spend with each patient ■ Capability and potential to accommodate increased patient volume ■ Reduced potential for errors during documentation, information transfers or transcriptions ■ Higher levels of patient satisfaction with the overall office experience ■ Lower chair costs through increased per patient profitability ■ A more productive, profitable, enjoyable practice. |

| TABLE 4 Challenges associated with integrating an existing practice: ■ Cost of new technologies ■ Instrument and equipment maintenance ■ Financial planning for instrument obsolescence ■ Training, familiarization with new instrumentation ■ Adjustments from traditional clinical approaches ■ Scheduling issues associated with new patient flow ■ Learning to deal with the multitude of issues associated with a paperless (EMR) office ■ Resistance to change. |

Challenges

A change of this magnitude carries with it significant challenges. Basic philosophies will have to be reassessed. Examples of such philosophical issues range from patient scheduling to office staffing and training, all the way to the increased use of technicians and delegation. Even hiring (and firing) will change as the nature of the practice changes. Some staff will adjust easily, some reluctantly and some not at all.

Table 4 includes a limited list of the challenges to be faced when integrating a practice, but every practice will have its own unique set of challenges based on professional issues, personal issues and the inherently unique characteristics that create the individual profile of every practice.

Most experts estimate that the timeframe for the efficient and effective conversion of a traditional practice into an EMR, integrated electronic automated practice could be as much as 2 to 3 years or longer. Given some of the federal mandates for 2010 and 2014, practices should have begun implementing the necessary changes already to qualify for the 2010 incentives. If your practice has done so and you're "in the process" or already have integrated, congratulations. You're in great shape. But that probably represents only about 10% of optometric practitioners. That leaves 90% of our profession in a challenging position.

Forced compliance and increased audits through 2014 and potential mandatory regulations thereafter won't be pleasant if a practitioner isn't prepared. The 2-year window from 2008 to 2010 is an important period for optometric practitioners to begin the conversion and be ready for the incentives offered in 2010. By then, practices should be, at the very least, in the process of integration, automation and EMR functioning. During the 4-year window from 2010 to 2014, practices should continue the conversion with a carefully planned timeline that includes a full conversion by 2014.

A wise planner will begin early and make "Best in Class" provider status a goal for 2010 and a fully integrated electronic automated practice the goal for 2014. Challenging? Yes. Doable? Absolutely!

Plans of Action

Every practice will have its own plan of action based on the specific nature and profile of the practice, but a few suggestions from some veterans may help guide the process.

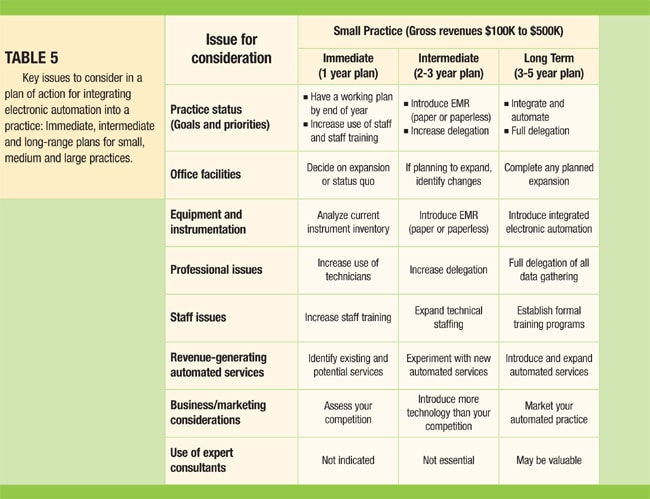

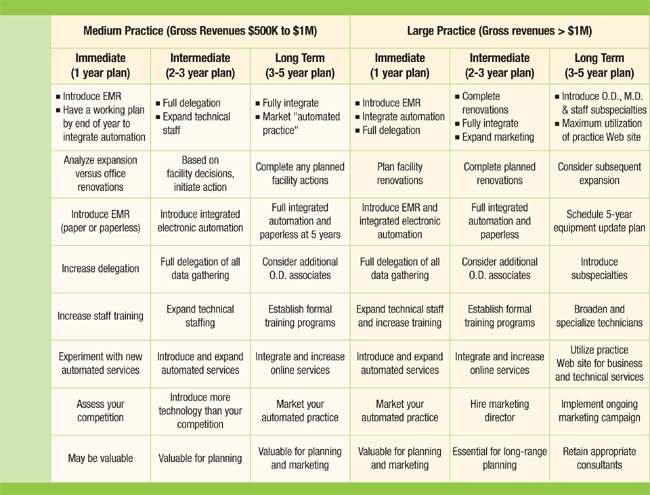

Table 5 is a chart of some of the key issues to consider in the immediate, intermediate and long-range planning for a small, medium or large practice. This is a limited list of general issues with general suggestions. A much more expanded list ultimately will be required in your planning, but this may help get things started in a positive direction.

Again, these are suggestions that don't take into consideration the very delicate (and emotional) issues unique to any practice and the process of change. Those considerations are too specific and personal for any chart and all too important to be assigned to anyone but the captain of the ship.

The integrated electronic automated practice may be part of your current mode of practice already. It may be a hard copy or a paperless model and it may include some form of delegation of data-gathering functions to trained and qualified technicians.

Whatever your current status, the future of your practice will be an ever-dynamic and ever-changing process in the years to come. Keep an open mind and somewhat regrettably — an open pocketbook — as you face the challenging decisions and actions that will be necessary for your patients' quality of care, your quality of life and the growth of your practice. OM

The authors are optometric associates with Nicolitz Eye Consultants in Jacksonville, Fla. Dr. Catania serves as a consultant to Marco Ophthalmics but none of the other authors have any financial interest in any of the products, systems or services mentioned in this article. The authors wish to thank the following physicians for their assistance regarding the concepts discussed in this paper: Ian Lane, O.D., Lorrie Lippiatt, O.D., Lance Mallott, O.D., and Julie Ryan, O.D.

| Reference 1. Department of Health and Human Services, "Benchmark Study Report on National Performance Review," 1997. |