practice management

Sizing Up SPECSAVERS

Crissa Shoemaker Debree, contributing editor

Here’s an inside look at one of the world’s fastest growing retail practices — and its impact on optometry.

When Carmelo Castiglione, MCOptom, first began practicing nearly 20 years ago, Specsavers, with its value-for-money model of eyeglass sales and exams, was criticized for devaluing the profession he worked so hard to enter.

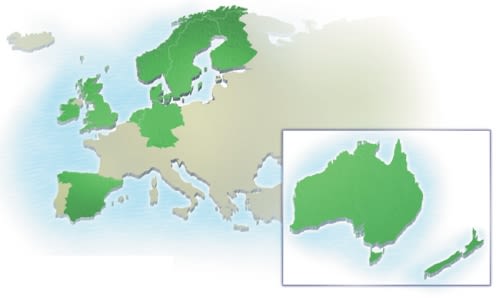

Today, Specsavers is the largest optical practice in the United Kingdom (U.K.), with more than 1,000 stores that together have captured an estimated 40% of the market. It’s the fastest growing retailer in Australia and New Zealand, where it’s become the number-one optical “chain” in a few short years. It’s also the leading dispensary in Norway, Ireland and Denmark. With its familiar green spectacle-shaped logo, Specsavers has been recognized as the most trusted brand in the U.K. by Readers Digest magazine.

“Today, they’re an accepted High Street (Main Street) optical group that has produced an excellent advertising and marketing campaign and a slogan that the general public use in day-to-day conversation,” says Dr. Castiglione, who operates an independent practice in Surrey, a county in Southeast England. “When it comes to purchasing spectacles from my practice, these words are often mumbled: ‘Is it buy one get one free?’”

At Specsavers, the answer is “yes.”

The company first introduced its two-for-one pricing in the 1980s. In so doing, Specsavers, through its network of joint venture practices (each store is an independent company half-owned by Specsavers), has transformed the way the public in the U.K. buys glasses. Critics say Specsavers’ promises of low costs can be deceiving — extras make spectacles more expensive than advertised. But proponents say the company’s large buying power helps keep costs low.

The company has become so well known that its advertising slogan, “I should have gone to Specsavers,” has become an everyday phrase. It’s even shown up in pop songs.

A humble start

For its size, however, Specsavers’ beginnings are humble.

U.K. government deregulation in the 1980s allowed opticians and other professionals to advertise their products and services for the first time. Optometrist Doug Perkins and his wife, Mary, both of whom had retired after selling a small chain of value-for-money opticians offices, saw opportunity. They opened the first Specsavers in 1984 in the spare bedroom of their home in Guernsey.

By forming joint venture stores with opticians and optometrists, Specsavers grew rapidly. It reached 100 stores within the first four years. It grew to 200 stores in 1993, then 300 in 1995. In 2005, it had 700 stores.

Specsavers opened its first stores in the Netherlands in 1997. Sweden, Denmark and Norway followed in 2004 and 2005. In 2006, it opened its first stores in Spain. In 2007, Specsavers opened its first stores in Finland and then Australia, which has become the company’s second-largest market behind the U.K.

Today, there are more than 1,500 Specsavers stores in Europe, Australia and New Zealand. Sales surpassed £1.5 billion (about $2.4 billion) last year, an increase of 10.3%. That same year, Dame Mary Perkins became the first female billionaire on The Sunday Times’ list of the wealthiest people in the U.K. with a net family worth of more than £1.15 billion (about $1.79 billion).

Through a spokeswoman, Specsavers declined multiple requests to comment for this article. However, the company’s annual reports, along with joint venture prospectuses, provide a picture of the company’s operations and growth.

A start at Specsavers

The typical practice costs roughly £150,000 ($240,000) to start, although the figure varies based on location, size of practice and other factors, the company says in its partnership brochures. Independent owners (optometrists and/or opticians) are expected to have at least £20,000 in liquid assets each to loan to the new business; Specsavers makes a similar loan. The company also can make a five-year loan for capital expenditures that is paid out from store profits, typically in a three-year period.

Stores can be owned by a sole optician/optometrist or a group. Each new practice is a separate company. When formed, an equal number of “A” shares and “B” shares are issued. “A” shares are owned by the practice owner or partners. “B” shares are owned by Specsavers. Specsavers also sets up similar arrangements with existing practices in which the practices would transition from independent ownership to the Specsavers’ model of joint venture ownership — a model that particularly helped the company’s growth in Australia, where 80 of the 260 stores that opened in the first year were conversions.

“A” shareholders are charged with the day-to-day running of the stores. “B” shareholders — Specsavers — provide support services, including IT, legal and payroll. Specsavers does not share in profits; rather, the company receives a management fee of about 16% of monthly turnover in return for its services.

If the partners wished to sell the practice, they would sell their “A” shares, leaving Specsavers to partner with the new owners.

“All clinical decision are ours,” says Russell Dawkins, MCOptom, who owns a Specsavers store near London along with an optical partner. “It is actually a great company to belong to. There is no interference in day-to-day running, if you’re doing a good job. And why would you not want to?”

Dr. Dawkins was a locum optometrist before making the decision to open a Specsavers location.

“Essentially, I’m running my own business,” he says. “But I don’t have to worry about property or operation issues on my own. They even take care of payroll. At the end of the day, it’s our store, and we’re responsible for our performance.”

Clinical and retail decisions

That means the owner makes daily decisions, from clinical policy directives to what time to open the retail store, Dawkins says. They also make the call on — and foot the bill for — equipment to purchase.

On the retail side, Specsavers stores offer about 2,000 different styles and colors of frames through its private brand, Osiris, and designers, such as Tommy Hilfiger, Quiksilver, Roxy and Missoni. Partners are required to stick with those brands. Lenses are manufactured under the Pentax brand, although, Dr. Dawkins says, store owners can make their own decisions on which lenses to offer from preferred vendors.

Specsavers continues to grow. In 2010 it launched a digital hearing aid business and has become the largest private seller of digital hearing aids in the U.K. It continues opening stores, including in supermarkets.

There’s no indication the company’s growth plans include the United States or Canada. But they would be met with stiff competition here, says Janice Mignogna, director of the Bennett Center for Business and Practice Management at the Pennsylvania College of Optometry.

“To introduce another type of practice like that would not be popular with the general private practice optometrist,” she says. “We have so many (practices). Walmart. Target. They are moving in everywhere. It’s supposed to be, promotion-wise, go there, you can get your glasses, they’re cheaper, they’re this. It’s a really big competition for private practitioners.

“The public’s perception is that, I’ll go there and get just as good an eye exam. Mostly they go for convenience — it’s in the mall, it’s down the street. They don’t normally go because of the doctors’ reputation. They go because it’s convenient to where they’re traveling.”

Dr. Castiglione, the U.K. optometrist, echoed the same complaints about competing against Specsavers’ low costs.

The model works, but…

“Clearly, their business model works,” he says. “The public are mesmerized, putting them into a trance and before they know it they have spent more on their glasses than they originally thought/bargained for. The independent, service-led practitioner who provides a decent job — who gets to know the patient and understands their needs — is often left scratching their heads thinking why on earth would a person go to an establishment that sees a patient as just another number?”

Recently, Specsavers began offering eye test vouchers for £5 (about $8).

“They have had a significant impact on public perception of eye care and eyewear,” Dr. Castiglione says. “Unless the public are educated in the products and services offered by their local independent practitioner, they simply do not know the difference. They have tapped into a market — that is, low-cost products and services — that right now resonates with the consumer. “After all, we are in a recession,” says Dr. Castiglione. “Their current low-cost eye test vouchers are quite simply insulting — yet it gets the ‘customers’ through the door,” he adds.

Still, Dr. Castiglione says he would remain an independent practitioner.

“Being independent allows me to choose products and services which I feel fit for my practice and ultimately my patients,” he says. “Yes it perhaps requires decisions to be made, but at least I am in control.”

Shimir Patel, MCOptom, worked as a resident optometrist for a Specsavers practice for nearly three years. Eighteen months ago he opened his own, independent practice in Essex.

“I think Specsavers is a very good model, but it wasn’t for me due to the constraints with respect to management, lack of control and the speed of the number of new Specsavers practices opening within a short space of time,” Dr. Patel says.

He describes the current optical market as “survival of the fittest.”

“I’m orienting my practice so I don’t eventually compete against them, but rather build my practice’s own niche clientele that deals with high-end products and a greater emphasis on clinical care,” he says. OM

| Ms. DeBree is a business reporter at The Intelligencer & Bucks County Courier Times in Pa. Send comments to optometricmanagement@gmail.com |