Treating anterior uveitis is an art and a science: Careful observation for recurrences or chronic disease, paired with quick intervention, are crucial to preventing irreversible vision loss.

Here, I provide a primer on the condition and its management.

PRIMER

Anterior uveitis is one of the most common forms of intraocular inflammation.1,2 Classified as acute or chronic, it is more prevalent in males and occurs between age 20 and 50, with symptoms of ocular pain, photophobia and, sometimes, blurry vision. That said, the condition can be asymptomatic. Differential diagnoses include conjunctivitis, episcleritis, keratitis, intraocular foreign body, leukemic infiltrates and more widespread ocular inflammation. The complications of the condition are band keratopathy, cataracts, cystoid macular edema and glaucoma.

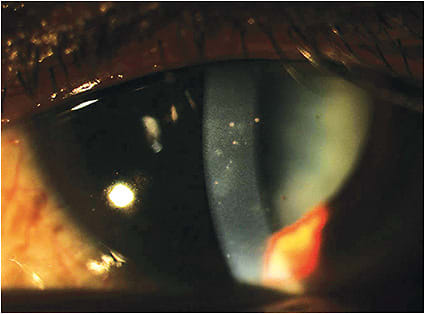

- Acute classification. Miotic pupil, white blood cells and protein flare within the anterior chamber (AC) and reduced IOP comprise this form.3 Uveitis is either non-granulomatous (small, white keratic precipitates [KP]) or granulomatous (mutton-fat KPs and iris nodules). However, initial presentation can often change, with a conversion to either.4 Non-granulomatous anterior uveitis is often idiopathic or may be associated with an HLA-B27 condition, such as Psoriatic arthritis.2,5 Viral causes should also be considered, in which case the presentation tends to be unilateral with increased IOP, and is likely to have other identifying features (e.g. skin involvement, immune system compromise).

- Recalcitrant, or chronic, classification. Findings such as pigmented KPs, iris atrophy, synechiae, hypopyon, band keratopathy and a mismatch of symptoms with degree of AC reaction (e.g. moderate AC reaction without any symptoms) are consistent with chronic uveitis.1,6

While a suggested 48% to 70% of anterior uveitis cases are thought idiopathic, other etiologies should first be carefully considered.6,7 Anterior uveitis can occur from ocular trauma, systemic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis, HLA-B27 conditions (50% of noninfectious acute and recurrent uveitis cases), Lyme disease, toxoplasmosis and toxocariasis, viral entities (herpes simplex or zoster, cytomegalovirus or rubella) and, rarely, Behcet’s disease and Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis. Bilaterality, chronicity, or recurrence, defined as cases with an interruption of at least three months without treatment, should prompt a more detailed review of systems.5,8 A rare but serious complication of a malpositioned intraocular lens, uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome should be considered in post-cataract extraction patients who have chronic and/or recurrent inflammation, hyphema and increased IOP.9

A true vitritis, posterior uveitis or panuveitis is associated with potentially devastating visual consequences, if left untreated and, therefore, must be ruled out with a dilated fundus exam on any patient demonstrating anterior uveitis. Furthermore, signs of posterior segment involvement, such as periphlebitis, retinitis or optic neuritis can help to identify the etiology.

MANAGEMENT

Management of anterior uveitis consists of the following:

- Anterior segment photography. This aids in documenting the condition at the initial visit, so the optometrist can monitor carefully for regression. Corneal endothelial spectral microscopy can aid in observing for endothelial changes, and anterior segment OCT, as well as high-resolution ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM), may be useful in watching for reduction in choroid and ciliary body thickness.10

- Cycloplegic. Alleviating symptoms, a cycloplegic quiets the ciliary body, stabilizing the blood aqueous barrier by decreasing the permeability of the vasculature and, therefore, reducing the anterior chamber reaction.2 A cylcoplegic may also prevent synechiae formation. In the case of acute posterior synechiae, O.D.s can add 10% phenylephrine in an attempt to break it, assuming there are not contraindications, such as heart disease or elevated blood pressure. This can be done simply by instilling one drop in office, or more aggressively by soaking a cotton-tipped applicator with both a strong cycloplegic and the 10% phenylephrine combined and allowing it to sit within the inferior fornix for up to 15 minutes. Successful synechiae breaks will typically manifest within the next 24 hours.

- Topical corticosteroids. Employed to reduce inflammation, the initial dosing in the acute classification is typically one corticosteroid drop hourly while awake, until the optometrist eventually observes less than five cells in the anterior chamber.1 (Patience is a virtue here. In severe cases, it can take weeks for the inflammation to subside.) Measuring the IOP at each follow-up is also important for those patients who are steroid responders. Non-generic corticosteroids, which are FDA approved for the treatment of idiopathic uveitis, can be chosen based on scheduled dosing and compliance barriers, cost, sensitivity to preservatives and risk factors to increased IOP.

Of particular importance: When prescribing, educate the patient that the results are highly sensitive to compliance with dosing, as well as the shaking of the drug bottle. Optometrists can reinforce this by informing the patient that failure to adhere increases risk for the complications outlined above.

At a one week follow-up, an ideal response to the steroid will result in at least a 50% reduction in the number of cells from the initial visit.1 Corticosteroid tapering should be slow and methodical, typically decreasing the dose to every two hours for up to two weeks; followed by four times a day for two weeks; twice a day for two weeks; and once a day for two weeks, with careful observation and a keen eye for a flare-up. After noting an ideal response, O.D.s can inform the patient that adherence to the prescribed treatment is the reason for this outcome, increasing the likelihood the patient will continue to comply. Finally, consider adding an “alert” note to the acute anterior uveitis patient’s chart, should he call the office on, say, Friday at 4:45, with what could be a recurrence, so staff will not put him off.

- Further testing and referral. When a patient presents with recalcitrant, or chronic anterior uveitis, the O.D. should suspect an inflammatory or infectious cause, lack of response to corticosteroids or non-compliance to the prescribed corticosteroid. For the former, the patient history is the most useful tool in determining the direction to pursue for diagnostic laboratory testing. For example, a chronic anterior uveitis patient who demonstrates a cough may have tuberculosis or sarcoid and, thus, should be referred for a chest x-ray, purified protein derivative, angiotensin converting enzyme and lysozyme tests to be reviewed by the primary care doctor. When a link is discovered, the O.D. should document the uveitis using codes specific to its etiology (e.g. sarcoidosis, syphilis, herpes, toxoplasmosis and many others) most of which are located within the A and B chapters of the ICD-10. (See https://go.cms.gov/2HeTIdN ). In the case of the latter, a retinal consultation for an injectable or implantable steroid should be considered. These long-term steroids are excellent solutions for the inflammation, however must be chosen wisely, as they have the unfortunate adverse effects of increased IOP and cataracts.

CATCHING THE CULPRIT

Making any systemic connection is critical not only to determine an underlying cause, which may itself need attention, but also to effectively manage the uveitis — some may require oral or subconjunctival steroids, an antiviral or other immunosuppressants to reach total resolution. Stay tuned, as newly discovered genetic markers associated with anterior uveitis may influence future therapeutic interventions. OM

REFERENCES

- Huang JJ, Gau PA. Ocular Inflammatory Disease and Uveitis Manual. Diagnosis and Treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010:1-9.

- Kabat AG. Uveitis. In: Barlett J, Jaanus S, editors. Clinical Ocular Pharmacology. 5th ed. St Louis: Elsevier; 2008: 587-699.

- Relvas LJ, Caspers L, Chee S, Zierhut M, Willermain F. Differential diagnosis of viral-induced anterior uveitis. Ocular Immunol. and inflamm. 2018: 26: 726-31

- Herbort CP. Appraisal, work-up and diagnosis of anterior uveitis: a practical approach. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009; 16: 159-67.

- Rosenbaum JT. Uveitis in spondylarthritis including psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2015; 34: 999-1002.

- Gutteridge IF, Hall AJ. Acute anterior uveitis in primary care. Clin Exp Optom. 2007; 90: 390.

- Gritz DC, Wong IG. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111: 491-500.

- Jabs DA, Nussenblat RB, Rosenbaum JT. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature (SUN) for reporting clinical data – results of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005; 150: 509-516.

- Foroozan R, Tabas JG, Moster ML. Recurrent microhyphaema despite intracapsular fixation of a posterior chamber intraocular lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003; 29: 1632–35.

- Siak J, Mahendradas P, Chee SP. Multimodal Imaging in Anterior Uveitis, Ocul. Immunol Inflamm., 2017; 25: 434-46.

- Foster CS, Davanzo R, Flynn TE, McLeod K, Vogel R, Crockett RS. Durezol (Difluprednate Ophthalmic Emulsion 0.05%) compared with Pred Forte 1% ophthalmic suspension in the treatment of endogenous anterior uveitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 26: 475-83.