Optometrists play a significant role in the successful management of diabetic patients by interpreting diagnostic data, staying current on, providing patient education about and implementing treatment (in states where scope of practice laws enable them to) and making timely and appropriate referrals.

INTERPRETING DIAGNOSTIC DATA

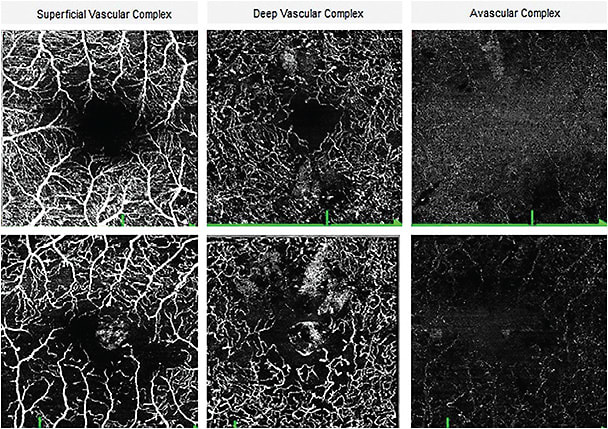

Scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, retinal photography (including ultra-widefield fundus imaging), fluorescein angiography and non-invasive OCT-A have all assisted the primary care O.D. in detecting pathology and making management decisions.1 (See “Diagnose Diabetic Eye Disease,” p.20, for more device information.)

STAYING CURRENT

Current treatment options are based on the type of diabetic eye disease present:

1 Diabetic Macular Edema

- Laser treatment. The Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy study (ETDRS) demonstrates patients who met the criteria of having clinically significant macular edema (CSME) benefited from laser treatment, with 50% achieving visual stability. (CSME is based on visible retinal thickening evident clinically, not just visible macular edema on OCT imaging.)2 This type of treatment utilizes thermal laser energy, leaving permanent scarring and damage to the tissue treated. Patients may have reduced vision and sco-tomas from the laser treatment itself and also are at increased risk of choroidal neovascularization from laser scarring. Ideally, laser treatment today may be used to target localized microaneurysms a safe distance from the fovea in those with localized diabetic macular edema (DME) areas.

- Anti-VEGF injections. Multiple studies on anti-VEGF injections show they stabilize vision and have the potential for visual gains in patients who have DME.3-7 Potential complications include: superficial punctate keratitis, corneal abrasion, subconjunctival hemorrhage, traumatic cataract, retinal detachment and endoph-thalmitis, with the more severe and sight-threatening complications being very rare. The decision to prescribe this treatment depends on a variety of factors that may include the amount and location of DME, the patient’s VA and symptoms, the overall level of retinopathy, the patient’s health status and blood sugar control and the patient’s willingness to undergo treatment. Anti-VEGF injections are the most commonly used first line treatment in DME patients, and would be an appropriate treatment choice for any patient in whom a physician considers the DME to be sight threatening.

The anti-VEGF medications used for DME are aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals), ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech) and bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech) (off label). The number of anti-VEGF injections needed varies per trial, but they may be required for an extended period of time.3-7 - Intravitreal steroid injections. Multiple trials show the benefit of intravitreal steroid injections in those with DME, including improved visual function and improved macular thickness.8-12 Their potential side effects include cataract formation and glaucoma.8-12 Steroidal medications may be beneficial in DME patients who have a suboptimal response to anti-VEGF agents.12,13 In addition, sustained-release steroid medications, such as dexamethasone intravitreal implant (Ozurdex, Allergan) and fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant (Iluvien, Alimera Sciences) may be used alone or in conjunction with anti-VEGF treatments to reduce the overall number of injections needed.9

- Topical drugs. Some evidence suggests the benefit of improved VA and macular thickness with topical NSAIDs and steroids in the treatment of DME, stemming primarily from uncontrolled trials and retrospective case studies or case series.14,15 However, at this time, treating DME with topical medications is not standard of care.

- Oral supplementation. The Diabetes Visual Function Supplement Study shows high-dose antioxidants may benefit color vision and contrast sensitivity in DME patients.16 How this relates to real-world visual function and long-term patient outcomes remains unclear.17 For primary care O.D.s considering this route, the number of medications a patient is already using and the potential side effects of oral supplementation should be assessed. For example, vitamin E and fish oils reduce blood clotting, so caution should be taken in those using systemic blood thinners; zinc is now implicated in the progression of Alzheimer's disease; and supplements can cause gastrointestinal side effects.

2 Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR):

- Panretinal photocoagulation (PRP). Trials, such as the Diabetic Retinopathy Study (DRS) and the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) show a significant visual benefit of using PRP to treat PDR by greatly reducing the risk of severe vision loss (VA worse than 5/200) in those who were treated vs. those in the observation group.2,18 In fact a few years into the DRS trial, the protocol was changed to treat those in the observation group, due to their high risk of severe vision loss without treatment. The DRS suggests treatment of patients who have certain high-risk characteristics, such as neovascularization of the disc (NVD) 1/4 to 1/3 disc area without vitreous or pre-retinal hemorrhage, NVD less than 1/4th disc area with vitreous or pre-retinal hemorrhage or neovascularization elsewhere greater than 1/2 disc area with vitreous hemorrhage or pre-retinal hemorrhage. The ETDRS recommends treating all such patients who have PDR and to consider treating those who have severe nonproliferative DR (NPDR) with this procedure as well.2,18 As mentioned, PRP treatment of those with high-risk PDR in the DRS significantly reduced their risk of developing severe vision loss, and PRP treatment of those with severe NPDR in the ETDRS reduced their risk of developing high-risk PDR. Risk vs. benefit of treatment must be more carefully considered in those with severe NPDR, as their risk of severe vision loss is not as high as those with high-risk PDR.

PRP uses thermal energy to destroy areas of peripheral retina to regress neovascularization. Extensive treatment can cause visual symptoms, such as decreased peripheral field and decreased night vision. - Anti-VEGF injections. The Protocol S study shows that ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech) alone can provide visual gains in these patients.19 In addition, the Panorama trial reveals that treating patients who have severe NPDR and no macular edema with periodic aflibercept (Eylea, Regeneron) injections regresses their retinopathy and decreases the risk of sight-threatening complications, such as traction retinal detachments and vitreous hemorrhage.20 These trials have led to the approval of both of these drugs for all forms of DR, with or without DME or neovascularization.

3 Other Vitreoretinal Diabetic Eye Disease

Tractional retinal detachments (TRD), vitreous hemorrhage or vitreomacular interface disease may require surgical repair. Visual outcomes in these patients are highly variable. Patients with vitreous hemorrhage may have excellent vision recovery after vitrectomy to remove the hemorrhage; however, patients with severe TRD may gain significant to little or no vision, which is why it is critical to catch diabetic eye disease before these more severe complications occur.21

PROVIDING PATIENT EDUCATION

In addition to discussing with the patient the potential treatment options outlined above, optometrists should also talk with patients about the severity of diabetic eye disease, what patients can do about it and when they’ll be referred to a surgeon for said treatments.

Regarding the severity of diabetic eye disease, we recommend: “You have a blinding disease that may require multiple treatments, along with a lifetime commitment to monitor the disease carefully. These treatments are not curative, but they can stabilize the disease and have potential for visual improvements. For your part, you can maintain good blood sugar control, eat a healthy diet, exercise regularly, follow up with your primary care physician (PCP) to manage your diabetes and follow-up with your eye doctor, all of which will play a role in preserving your vision.”

To that end, as a member of the diabetic patient’s health care team, O.D.s should obtain information regarding the PCP’s management, the patient’s smoking status and whether the patient has had consultations with a certified diabetic educator and a nutritionist. If not, recommendations and a referral to other health care providers may be made by the O.D.

Additionally, to improve the quality of life and overall prognosis, O.D.s should make every effort to communicate exam findings with the patient’s other health care providers. The protocols for communication have been defined in the AOA’s diabetic care guideline (bit.ly/3c9pyFx )

When it comes to the referral, O.D.s should educate patients about the signs of DME and/or retinal/iris neovascularization that are prompting the referral, as the former affects the central vision, and the latter can lead to total blindness. Discussing available treatment options may also be appropriate at this time. OM

REFERENCES

- Kernt M, Hadi I, Pinter F, et al. Assessment of diabetic retinopathy using nonmydriatic ultra-widefield scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (Optomap) Compared with ETDRS 7-Field Stereo Photography. Diabetes Care. 2012; 35(12):2459-2463.

- Early photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 9. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmol. 1991; 98(5):766-785.

- Brown DM, Nguyen QD, Marcus DM, et al. Long-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: The 36-month results from two phase III trials: RISE and RIDE). Ophthalmol. 2013; 120(10): 2013-2022

- Elman MJ, Qin H, Aiello LP, et al. Intravitreal ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: Three-year randomized trial results. Ophthalmol. 2012; 119(11): 2312-2318.

- Schmidt-Erfurth U, Lang GE, Holz FG, et al. Three-year outcomes of individualized ranibizumab treatment in patients with diabetic macular edema: The RESTORE extension study. Ophthalmol. 2014; 121(5): 1045-1053.

- Rajendram R, Fraser-Bell S, Kaines A, et al. A 2-year prospective randomized controlled trial of intravitreal bevacizumab or laser therapy (BOLT) in the management of diabetic macular edema: 24-Month data: report 3. Arch Ophthal. 2012; 130(8): 972-979.

- Heier JS, Korobelnik JF, Brown DM, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 148-week results from the VISTA and VIVID Studies. Ophthalmol. 2016; 123(11): 2376-2385.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. A randomized trial comparing intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide and focal/grid photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmol. 2008; 115(9):1447-1449.

- Campochiaro PA, Brown DM, Pearson A, et al. Long-term benefit of sustained-delivery fluocinolone acetonide vitreous inserts for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmol. 2011; 118(4): 626-635.e2.

- Callanan DG, Gupta S, Boyer DS, et al. Dexamethasone intravitreal implant in combination with laser photocoagulation for the treatment of diffuse diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmol. 2013; 120(9): 1843-1851.

- Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, et al. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmol. 2010; 117(6):1064-1077. e35.

- Elman MJ, Bressler NM, Qin H, et al. Expanded 2-year follow-up of ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmol. 2011; 118(4): 609-614.

- Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Liu D, et al. Effect of adding dexamethasone to continued ranibizumab treatment in patients with persistent diabetic macular edema: A DRCR network phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018; 136(1): 29-38.

- Russo A, Costagliola C, Delcassi L, et al. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for macular edema. Mediators Inflamm. 2013: 476525.

- Sahoo S, Barua A, Myint KT, Haq A, Abas ABL, Nair NS. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents for diabetic cystoid macular oedema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (2):CD010009.

- Chous AP, Richer SP, Gerson JD, Kowluru RA. The diabetes visual function supplement study (DiVFuSS). Br J Ophthalmol. 2016; 100(2): 227-234.

- Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Ardeshirlarijani E, Namazi N, Nikfar S, Jalili RB, Larijani B. Dietary antioxidative supplements and diabetic retinopathy; a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019; 18(2): 705-716.

- Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Indications for photocoagulation treatment of diabetic retinopathy: Diabetic Retinopathy Study Report no. 14. The Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1987; 27(4): 239-253.

- Gross JG, Glassman AR, Jampol LM, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A randomized Trial. JAMA 2015; 314(20): 2137-2146.

- Wykoff CC. Intravitreal aflibercept for moderately severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR): 2-Year Outcome of the Phase 3 PANOROMA Study. Data presented at: Angiogenesis, Exudation and Degeneration Annual Meeting; February 8 2020; Miami, FL.

- Gupta V, Arevalo JF. Surgical management of diabetic retinopathy. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20(4): 283-292. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.120003

- AOA Evidenced-Based Clinical Practice Guideline: Eye care of the Patient with Diabetes Mellitus: Second Edition. https://aoa.uberflip.com/i/1183026-evidence-based-clinical-practice-guideline-eye-care-of-the-patient-with-diabetes-mellitus-second-edition/0?m4= Accessed 8/19/20.