Let’s get back to the basics

As we close out 2021, and in the spirit of innovation (“to renew or alter”), what can we easily renew or alter in our practices that will help us diagnose and detect glaucoma progression sooner?

RENEWING APPLICATIONS

Mean IOP remains the greatest modifiable risk factor in the development1-2 and progression of glaucoma,3-6 so each mm Hg elevation matters1-7 in the patient’s risk analysis. Furthermore, we know from well-designed, population-based studies that IOP reduction decreases the risk of glaucoma development1-2 and progression.3-6 Importantly, these conclusions are applicable even in the lower end of the IOP spectrum, such that a 30% IOP reduction among patients who have a median IOP of < 20 mm Hg decreases their risk of glaucomatous progression.7

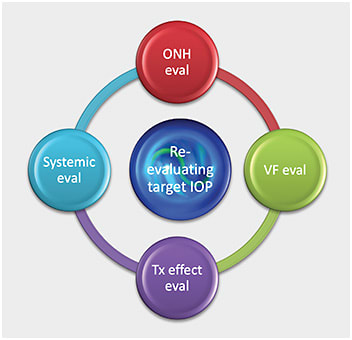

Renewing these applications in the clinical setting helps us more routinely develop a dynamic target IOP range based on four potentially ever-changing questions:8

- How does the optic nerve look with the current mean IOP?

- How do VFs look with the current mean IOP?

- How does the current treatment affect the patient’s quality of life?

- How does the current treatment affect the patient’s systemic health and residual life expectancy?

From these four questions, and based on clinical findings and patient responses, we can then alter our treatment plan and our target IOP range in three ways:8-10

- Increase the target IOP range.

- Decrease the target IOP range.

- Maintain the current range.

Continually re-evaluating the target IOP range helps us to ensure sufficient treatment to prevent glaucomatous progression, while avoiding any over-treatment that may affect quality of life.

ALTERING LIMITATIONS

Despite the significance of the patient’s IOP, we know these values have inherent limitations depending on the type of device utilized, time of day, provider technique, patient positioning and the patient’s ocular/systemic profile, to name just a few. As such, the IOP can often be overestimated (potentially leading to over-treatment) and underestimated (potentially leading to under-treatment).8,11 Most concerning of these scenarios is the resulting under-diagnosis of glaucoma based on an over-reliance of low or normal IOP readings.12 Quigley suggests that to prevent this mistake, we “kill the magic number”13 of 21 and consider and/or adjust the target IOP range based on the clinical findings.

HAPPY RENEW YEAR!

As we look to a new year, may we renew our efforts with this simple innovative resolution: Look at the optic nerve at every visit, and put the IOP and any associated treatment in the context of the optic nerve. A better awareness of the IOP applications and an altered approach to the common IOP limitations will help us diagnose glaucoma earlier and detect progression sooner. OM

References

1. Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):701–830. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701.

2. Miglior S, Zeyen T., Pfeiffer N, et al. Results of the European Glaucoma Prevention Study. Ophthalmology 2005;112:366-375. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.030.

3. Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(10):1268–1279. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268.

4. Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Niziol LM, Lichter PR, Varma R; CIGTS Study Group. Intraocular pressure control and long-term visual field loss in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(9):1766–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.047.

5. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):429-440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9.

6. Sommer A., Tielsch JM, Katz J, et al. Relationship between intraocular pressure and primary open angle glaucoma among white and black Americans. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1090-1095. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080080050026.

7. Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;26:487-497. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00223-2.

8. Weinbreb R.N., Brandt J.D., Garway-Heath D., et al. World Glaucoma Association Consensus Series 4 – Intraocular Pressure. Kugler Publications, The Hague, The Netherlands. 2007

9. Jampel HD. Target pressure in glaucoma therapy. J Glaucoma. 1997;6(2):133-8.

10. Sihota R, Angmo D, Ramaswamy D, Dada T. Simplifying "target" intraocular pressure for different stages of primary open-angle glaucoma and primary angle-closure glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018 Apr;66(4):495-505. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1130_17.

11. Davanian AM, Donahue SP, Mogil RS, Groth SL. Mask-induced Artifact Impacts Intraocular Pressure Measurement Using Goldmann Applanation Tonometry. J Glaucoma. 2021;30(3):e47-e49. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000001746.

12. Chan MPY, Khawaja AP, Broadway DC, et al. Risk factors for previously undiagnosed primary open-angle glaucoma: the EPIC-Norfolk Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021 Jun 25:bjophthalmol-2020-317718. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317718.

13. Quigley HA. 21st century glaucoma care. Eye (Lond). 2019;33(2):254-260. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0227-8.