Making the diagnosis of AMD goes well beyond your knowledge of the science. As optometrists, we are all aware that as many as 11 million people in the United States have AMD, according to a forecasting study of the disease, published in Epidemiology. So, the pickings aren’t slim.

That said, we can diagnose AMD early by implementing protocols that make the transition from suspicion to diagnosis smooth and pleasant for our patients. Such protocols engage patients, thereby increasing compliance, adding significant value to one’s practice and increasing patient loyalty. Here’s the protocol used in my practice.

ASK THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

When gathering the patient’s intake form, asking leading questions will help facilitate selecting the most “at-risk” candidates for AMD diagnostic testing. The important risk factors include age, smoking, family history/genetics, race, obesity and cardiovascular disease. Some of these risk factors may be obvious, but others must be asked of the patient. Often when we ask about smoking, in particular, I am questioned by my patient as to what importance this may have with regard to their eyes. This presents a great opportunity to elaborate on the role smoking plays in AMD. (For more on this topic, see bit.ly/1117SmokingCessation .) You should also be very comfortable, as a health care provider, in discussing the role of race and obesity as AMD risk factors. (More on risk factors at bit.ly/OM1220AMD .) Most people don’t correlate these risk factors with eye disease, so it is our responsibility to share this information with them. It also presents a wealth of data from which we can then move forward with AMD testing, as needed.

EMPLOY DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

AMD testing can come in one of two forms: screening and diagnostics.

Screening protocols for AMD include a selection of tests, such as dark adaptation, macular pigment optical density (MPOD) and genetic testing, performed on each patient who opts in to this offering, usually based on age, specifically, age 50- to 60-year-old patients. Practices unable to screen patients should have a testing protocol for those patients whose clinical exam makes them a candidate for the diagnosis of AMD, including the presence of drusen and/or RPE defects, night vision issues and/or metamorphopsia.

The following is a list of the various tests that may be performed to diagnose and/or monitor our AMD suspects or patients (in alphabetical order):

Contrast sensitivity. This measures the response of the visual system to a range of light intensities and levels of contrast that could be affected by the presence of central drusen.

Dark adaptation (DA). This measures rod intercept, the time it takes to transition from light to dark, providing functional assessment of AMD. DA is a biomarker for AMD.

Electroretinography/pattern electroretinogram. These measures retinal electrical activity, which can help diagnose certain retinal diseases, including AMD.

Fundus autofluorescence. This identifies metabolic dysfunction, leading to abnormal accumulation of lipofuscin in the RPE as well as areas of geographic atrophy.

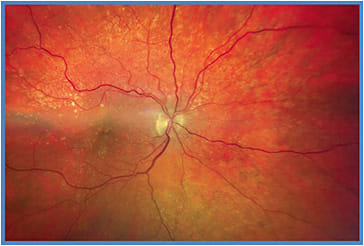

Fundus photography/imaging. This captures clinical findings, such as drusen and/or pigmentary disturbances to document what is seen clinically on exam. Often, the O.D.’s review of images will highlight findings that may be missed on examination.

Genetic testing. This assesses risk for AMD based on a patient’s genetic profile.

Microperimetry. This assesses retinal sensitivity and fixation behavior by providing simultaneous data on visual function and anatomical pathology.

MPOD. This assesses the level of carotenoids in the macula, a risk factor for developing AMD.

OCT/OCT-A. These aid in elucidating the presence of macular drusen, fluid or bleeding, in addition to other macula abnormalities, allowing us to diagnose abnormalities below the surface. OCT-A provides a non-invasive view of the choroidal vasculature, which is diagnostic of wet AMD.

EDUCATE PATIENTS

Realizing that so many wet AMD referrals are made when significant vision has already been lost, we stress with patients the importance of early diagnosis. Those patients who are at risk need to be well educated about the diagnosis and prognosis and typical frequency of testing needed. This will put them at ease when they return for testing and will help them understand the testing protocol and the possible need for nutritional supplementation and lifestyle changes.

Discussions about testing protocols, whether screening or diagnostic, should include:

- What is the name of the test?

- Why is this test being done/how will information from the test help with the diagnosis?

- How will patients feel during testing: Is the test “easy” for the patient, comfortable or can they anticipate some discomfort?

- How long will the test take?

- For longer tests, what kind of instruction can be expected during testing?

- What will be required of the patient?

- Will there be any lingering effects of the testing the patient should be made aware of?

It is important to explain both the results of the baseline test and any subsequent follow-up testing that will be required. For example, when a patient presents with macular drusen, excellent VA and normal DA, we explain that follow-up will occur annually with OCT and DA, along with a clinical exam. If a biomarker for AMD is detected, we place the patient on supplementation and discuss lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of disease progression. We tell these patients they will be followed every six months. In either case, baseline photography is performed and an Amsler grid is dispensed. These patients will become “regulars” in your practice, so relationship building is important to maintain compliance and peace of mind for them.

Additionally, our practice has created a comprehensive, but easy-to-understand, brochure on drusen and AMD, so patients fully understand the disease and potential for vision loss. We also discuss the treatment options, such as anti-VEGF injections, so patients have the full picture of how AMD is managed. Other options for AMD brochures include the NEI/NIH, American Optometric Association and American Academy of Optometry. It is helpful for your patient to leave with some written information, along with websites, to review what you may have shared with them. They can share the information with their family and be prepared to ask additional questions at their follow-up visit with you.

STAFF PREPARATION

Everyone — doctors, technicians, receptionists — should have information about testing and be prepared to answer patient questions, as patients often ask staff questions, thinking that they have more time to answer them than the doctor. Our staff is given a copy of our written material, so they know what information the patient is given. Our doctors educate them directly, and we often bring in outside speakers to educate them.

ADD VALUE

When a patient exhibits findings that make you suspect AMD, the outlined action steps can yield opportunities for both patients and your practice.

A practice protocol, a patient education plan and having the appropriate technology and staff can make diagnosing and managing AMD a smooth and pleasant experience, despite the seriousness of the diagnosis. OM