As the primary eye care providers, optometrists are on the forefront of diagnosing and effectively managing dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD). In doing so early in the disease process, we can work with the patient to prevent vision loss from late AMD. This is more important than ever, given the new treatment modalities on the horizon for dry AMD.

Here, I discuss how, specifically, to identify dry AMD early and then best manage these patients. (See Specific Dry AMD Case Examples below.)

DIAGNOSIS

The five action steps involved in identifying AMD early:

- Put it on your diagnostic radar. During the comprehensive eye exam, we should be conscious of the fact that dry AMD can be difficult to visualize and is under-diagnosed. In fact, a study by Neely et. al. shows approximately 25% of eyes diagnosed as normal, based on dilated eye examination by primary eye care physicians, had early-to-intermediate AMD revealed by fundus photography and trained raters. What’s more, a total of 30% of eyes that had undiagnosed AMD had large drusen, categorized as intermediate AMD, that would have been treatable with ocular nutritional supplementation, had it been diagnosed during the dilated fundus examination. The most common missed sign of AMD was drusen, likely because they are small, sparse or in isolation in early stages.1Further, let’s be sure we take into account the AMD risk factors associated with each patient, namely age (older than 50), race (caucasian), family history, gender (women), smoking status, comorbidity status (i.e., BMI, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia), poor diet, low macular pigment optical density (MPOD) and a sedentary lifestyle.2

- Schedule an AMD Consult. We should educate the patient on the concerning findings during their comprehensive exam and then schedule the patient to return for an “AMD Consult.” We can bill the consultation by time spent with the patient, perform additional testing as indicated, and allow ourselves the time needed to educate patients properly.

- Perform structural testing. This is comprised of fundus photography, fundus autofluorescence (FAF), macula OCT with OCT-A, and multispectral imaging.Baseline macula photodocumentation is appropriate for any size or amount of drusen found during fundoscopy. Photodocumentation provides an opportunity to carefully judge the size of drusen to stage AMD accurately. Something else to keep in mind: Photodocumentation is an effective tool for patient education, as it shows the patient their status of AMD and, therefore, the importance of the prescribed management.

- Employ the drusen rating scale. A universally accepted structural grading scale for clinical AMD has been in place since the Age-Related Eye Disease Study,3 and was simplified by the Beckman Initiative for Macular Research Classification Committee.4 Specifically, an eye that has either no drusen or drusen that is ≤ 63 μm with no pigmentary abnormalities is considered non-AMD. An eye that has drusen > 63 μm and ≤ 125 μm with no pigmentary abnormalities is considered early AMD. An eye that has a druse > 125 μm and/or any AMD pigmentary abnormalities is considered intermediate AMD. Finally, late AMD presents as geographic atrophy and/or neovascularization. We should not underestimate the challenges of sizing drusen with fundoscopy: 125 μm is about the diameter of the central retina vein at the disc margin, and a patient needs only one large druse to be considered to have intermediate stage AMD.

- Perform functional testing. AMD management should not be based on structure alone. Like glaucoma, it has functional deficits prior to or alongside structural damage. The functional testing for AMD is dark adaptation (see bit.ly/OMDarkAdapt ), contrast sensitivity (see “Add Contrast Sensitivity Testing for AMD,” at bit.ly/ContrastOM ) visual acuity, Amsler grid testing, and microperimetry (see “Diagnose AMD With Technology at bit.ly/microOM ). I find that dark adaptometry allows the practitioner to give the patient a 90% accurate diagnosis of drusen caused by AMD vs. drusen that develop normally with the aging process.

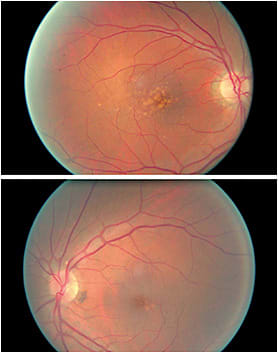

CASE 1

A 70-year-old white male, with a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and three cardiac stents with both eyes classified as intermediate AMD. This is because of the presence of large drusen. The small amount of drusen in the left eye can easily be overlooked during fundoscopy if the macula is not carefully examined or illumination is too bright or too dim.

MANAGEMENT

The four action steps involved in managing these patients effectively:

- Provide patient education. At the end of the comprehensive exam, I show the patient the findings that concern me in the baseline photograph, and I provide a comprehensive AMD educational handout. For the latter, I ask the patient to review it, and write questions in the margins to ask at their “AMD Consult” appointment. Patients who understand their condition are more compliant with mutually made treatment decisions.5 Therefore, education is paramount in managing AMD.During their “AMD Consult” appointment, I typically discuss the modifiable risk factors for AMD to prevent the condition from converting to wet AMD. For example, I explain that a study shows walking 12 blocks regularly decreases the risk of AMD by 30%, and that, in comparing extremes, those who practice an active lifestyle had a 70% reduced risk of AMD vs. those who practiced a sedentary lifestyle.6 Another example: I explain to smokers that those who quit the habit decrease their risk of AMD progression, with the timing of reduced risk dose and length of dependency.7 (See “Help Patients Quit Smoking” at bit.ly/QuitSmokingOM .) For a full list of modifiable risk factors, see “Managing AMD,” at bit.ly/AMDModFactors .

- Consider prescribing an ocular nutritional supplement. If the patient has intermediate AMD, it is recommended to add a high-quality ocular nutritional supplement, which may prevent disease progression. (For advice on what to recommend and how, see “Prescribing Supplements for AMD,” at bit.ly/AMDSuppOM .) A brand-specific recommendation should be made to avoid patient confusion with the many OTC options available. Remember: Nutraceuticals are not FDA regulated, so we should ensure our patient is receiving the correct ingredients and dosage of the recommended supplementation.

- Establish a follow-up appointment schedule. Follow-up frequency is important because studies show that the VA at the initial wet AMD diagnosis is about what the vision will be one and two years after beginning anti-VEGF injections.8-12 Follow-up frequency is determined by how likely the patient is to progress in their disease. We should monitor closely (e.g., three to six months, depending on current macular status and individual rate of progression over time) those patients who have progressing size and number of drusen, serially delayed dark adaptation, a strong family history of AMD and genetic predisposition for wet AMD, and who develop retinal pigment epithelial changes.In addition to follow-up and testing in-office to detect the earliest sign of conversion to wet AMD, home monitoring is available via the ForeseeHome, which uses preferential hyperacuity perimetry, and alerts the optometrist if a statistically significant change in metamorphopsia occurs between visits. From there, the patient is called and scheduled for an urgent dilated exam to determine whether the change is due to wet AMD conversion. This gives me comfort to extend time between office visits if every three months is burdensome for patients.

- Refer immediately when conversion to choroidal neovascular membrane is noted. This is when anti-VEGF treatment will need to be initiated by a retinal specialist. That said, all patients should still be managed by their OD at regular intervals for their overall eye health and management of visual function. If the patient’s wet AMD is progressing and, therefore, causing vision loss, we should discuss vision aids, such as glare protection, tints, yoked prism, appropriate lighting, higher-add powers and adjusting working distance, and consultations with a low vision specialist and an occupational therapist.

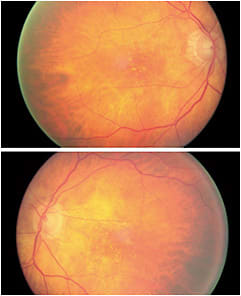

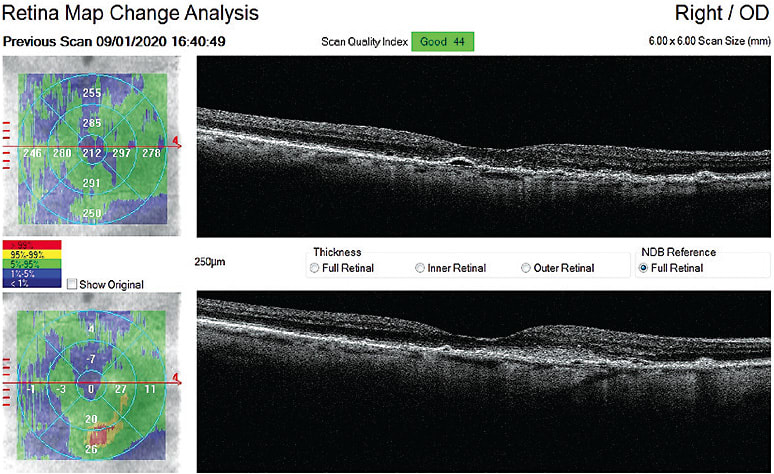

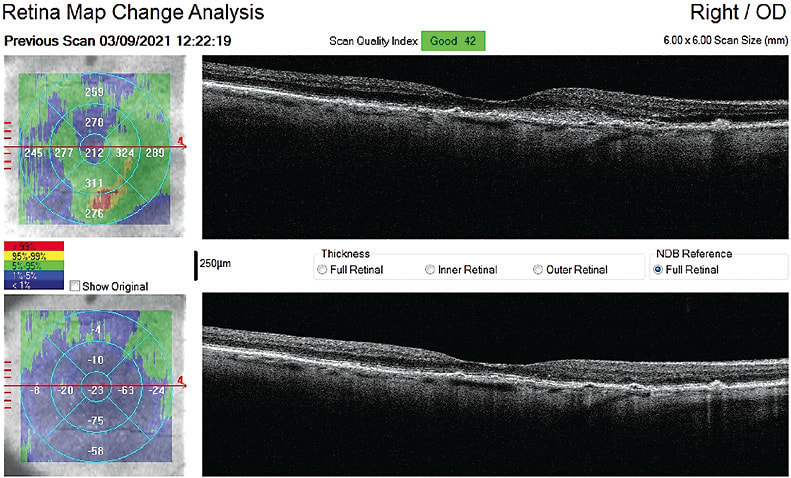

CASE 2

This is an 86-year-old female. I have diagnosed and managed her intermediate AMD since 2014. Her dark adaptation was severely delayed and progressed rapidly over a two-year period. I monitored her every four months. At a pre-scheduled AMD visit she was 20/25 OD and 20/30 OS. A suspected CNVM was forming para-macular, imaged on the OCT as a fibrovascular opacified intraretinal lesion OD.

She was promptly referred to a retina specialist and received one anti-VEGF injection, which resolved all fluid. She then underwent cataract surgery and had another injection after. We monitored carefully and she never developed further CNVM or leakage. She had three injections total because of how early anti-VEGF treatment was initiated.

The macula did have some atrophy develop over time, but her vision after cataract surgery significantly improved and has remains 20/20-3 OD and 20/25 OS at her most recent visit July 2022.

THE ROLE OF A LIFETIME

By diagnosing dry AMD early and managing it effectively with the action steps provided above, we can enable these patients to maintain good vision. Further, by detecting wet AMD conversion at the earliest possible sign, making that referral for intervention, and consistently monitoring the quality of our patients’ vision, we can significantly impact the quality of someone’s vision and life. OM

REFERENCES

- Neely D, Bray K, Huisingh C, Clark ME, McGwin G, Owsley C., et al. Prevalence of Undiagnosed Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Primary Eye Care. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(6): 570-575. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0830.

- Klein R, Peto T, Bird A, Vannewkirk MR. The epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(3):486-95. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.069.

- Seddon JM, Sharma S, Adelman RA. Evaluation of the clinical age-related maculopathy staging system. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(2):260-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.11.001.

- Ferris FL, Wilkinson CP, Bird A, et al. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. 2013 Apr;120(4):844-51. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.036.

- Scheffer M, Menting J, Roodbeen R, et al. Patients and health professionals’ views on shared decision-making in age-related macular degeneration care: a qualitative study. College Optom. 2022;00:1-8.

- Knudtson MD, Klein R, Klein BEK. Physical activity and the 15-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006 Dec;90(12):1461-3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.103796.

- Thornton J, Edwards R, Mitchell P, Harrison RA, Buchan I, Kelly SP. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: a review of association. Eye (Lond). 2005;19(9):935-44. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701978.

- Ying GS, Huang J, Maguire MG, et al. Baseline predictors for one-year visual outcomes with ranibizumab or bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013; 120(1):122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.042.

- Chew EY, Clemons TE, Bressler SB, et al. Randomized trial of a home monitoring system for early detection of choroidal neovascularization home monitoring of the eye (HOME) study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(2):535-44. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.027.

- Steinle N, Du W, Gibson A, Saroj N. Outcomes by Baseline Choroidal Neovascularization Features in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Post-Hoc Analysis of the VIEW Studies. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(2):141-150. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.07.003.

- Ho AC, Kleinman DM, Lum FC, et al. Baseline Visual Acuity at Wet AMD Diagnosis Predicts Long-Term Visual Outcomes: An Analysis of the IRIS Registry. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2020 ;51(11):633-639. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20201104-05.

- Martin DF, Maguire MG, Fine SL, et al. Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) Research Group. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(7):1388-98. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.053.