Optometrists frequently encounter patients presenting with puzzling and challenging signs and symptoms, which may be attributed to autoimmune diseases. This article aims to provide a practical and clinically relevant approach to understanding autoimmune diseases, their impact on ocular tissues, and the assessment and management challenges associated with these cases.

Definitions and discussion

Autoimmune disorders arise from dysregulation of the immune system, leading to the immune system attacking and damaging healthy body tissues.1 These disorders can affect various structures, including joints, muscles, skin, endocrine glands (e.g., thyroid, pancreas), red blood cells, blood vessels, and connective tissue.

Ocular tissues, rich in these structures, are directly or indirectly impacted by the resulting damage. Approximately 80 autoimmune conditions have been identified, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Sjögren’s syndrome, Graves’ disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), sarcoidosis, and type I diabetes, all of which can have ocular complications (Table).2

| Autoimmune Condition | Ocular Manifestation |

| Addison’s Disease | Conjunctivitis, episcleritis, hemianopia, optic atrophy, strabismus, retinopathy, vision agnosia, visual loss |

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | Uveitis |

| Antiphospholipid Syndrome | Optic neuropathy, vaso-occlusive retinopathy |

| Behçet’s Disease | Uveitis |

| Celiac Disease(gluten-sensitive enteropathy) | Cataracts, dry eyes, nyctalopia, pseudotumor cerebri, retinopathy, vitamin A deficiency, vision loss |

| Dermatomyositis | Eyelid/conjunctival edema, retinopathy, uveitis |

| Enteropathic Arthritis (Inflammatory Bowel Disease) |

Episcleritis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, uveitis |

| Giant Cell Arteritis | Amaurosis fugax, diplopia, optic neuritis, retinal artery occlusion |

| Graves’ Disease and Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis | Decreased visual acuity, keratitis, lid lag and retraction, loss of color vision, proptosis/exophthalmos, reduced visual fields, relative afferent pupillary defect |

| Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis | Uveitis (Iritis) |

| Multiple Sclerosis | Afferent pupillary defect, optic neuritis, visual field defect |

| Myasthenia Gravis | Diplopia, ocular motility deficit, ptosis |

| Pernicious Anemia | Anemic retinopathy |

| Polyarteritis Nodosa | Episcleritis, optic neuropathy, scleritis |

| Psoriatic Arthritis | Conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis |

| Reactive Arthritis (previously Reiter’s Syndrome) |

Conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Choroiditis, episcleral nodules, episcleritis, keratitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, retinal vasculitis, scleritis, ulcerative keratitis |

| Sarcoidosis | Conjunctival nodules, cranial nerve palsies, enlarged lacrimal glands, optic neuropathy, uveitis, vascular retinopathy |

| Sjögren’s Syndrome | Keratoconjunctivitis sicca |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | Amaurosis, conjunctivitis, episcleritis, hemianopia, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, ischemic optic neuropathy, keratitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, oculomotor abnormalities, optic neuritis, proliferative retinopathy, pupillary abnormalities, retinal hemorrhages, retinal vasculitis, scleritis, uveitis, visual hallucinations |

| Type I Diabetes | Retinopathy |

| Wegener’s Granulomatosis | Corneal ulcer, orbital cellulitis, optic neuropathy, proptosis, uveitis |

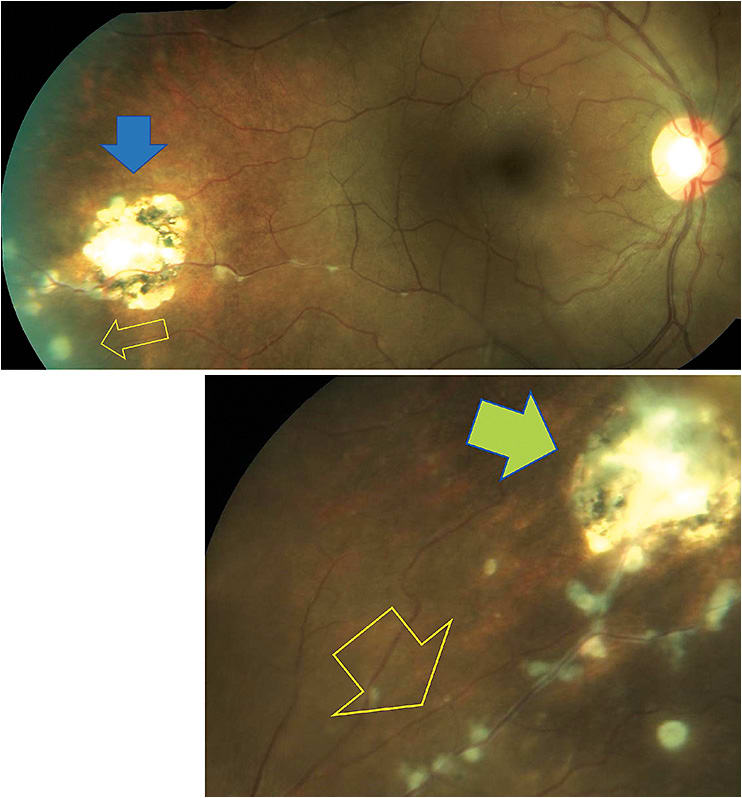

The prevalence of autoimmune diseases is staggering, affecting millions worldwide. The exact cause of autoimmunity remains unknown, although genetic and environmental factors are believed to play a role.3 One theory is that bacteria, viruses, drugs, or changes in a patient’s circumstances can trigger these immune system dysfunctions and imbalances, exacerbating the condition.3 In some cases, a change in the patient’s circumstance may worsen their condition. An example of this is the case of a 36-year-old Black female with a history of sarcoidosis in remission, which worsened during her pregnancy and caused visual symptoms associated with posterior uveitis and retinal vasculitis (Figure 1).

Ocular manifestations of autoimmune diseases

Autoimmune diseases can involve various ocular structures and present with a wide spectrum of manifestations. Ocular manifestations of autoimmune diseases can occur through direct or indirect mechanisms.

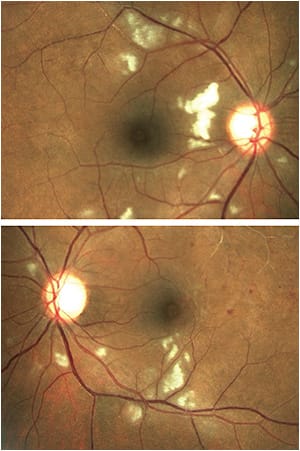

RA, for instance, may lead to scleritis, episcleritis, or dry eye disease. Sjögren’s syndrome, characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands, commonly causes dry eye disease and keratoconjunctivitis sicca. SLE, a connective tissue disease, can alter the connective tissue of the eye, resulting in scleritis. Simultaneously, associated hematologic and vascular diseases can cause retinal hemorrhages and vaso-occlusive retinopathy (Figure 2). Similar mechanisms apply to other conditions listed in the Table on page 37.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing autoimmune disorders can present a “chicken or the egg” dilemma. Patients may present with a history of autoimmune disease, requiring optometrists to screen and investigate possible ocular manifestations (as noted in the Table). Alternatively, patients may present with ocular symptoms and signs, such as uveitis, which necessitate further systemic investigation to rule out an underlying autoimmune disorder, such as RA.

Imaging techniques, including optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fluorescein angiography (FA), play an important role in assessing ocular involvement in autoimmune diseases. OCT allows for a detailed evaluation of retinal and choroidal changes, while FA aids in the identification of vascular abnormalities, such as retinal and choroidal vascular changes associated with conditions, such as sarcoidosis.4

Treatment and management

Managing these conditions can be challenging, as doing so often involves treating both the ophthalmic and systemic components. Coordinated comanagement is essential for optimal outcomes. Since autoimmune diseases generally have no cure and exhibit a chronic, waxing-and-waning nature, patients may require lifelong therapies and endure permanent physical and ocular disabilities.

Treatment approaches can range from supportive therapies for reducing symptoms to immunomodulation and biologics aimed at minimizing tissue damage.

One medication used for treatment is hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, Sanofi), commonly used for RA and SLE. While hydroxychloroquine rarely induces macular damage at low doses, irreversible retinal toxicity can occur in long-term users.5 Other systemic medications also come with side effects. For instance, corticosteroids are often prescribed to alleviate inflammation and associated effects, but their long-term use can result in significant ocular complications, including cataracts, glaucoma, and central serous retinopathy.6 They can also cause non-ocular complications, such as elevated blood sugar levels and Cushing’s syndrome.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, like adalimumab (Humira; AbbVie) and methotrexate, used to manage various autoimmune conditions, can have serious ocular side effects, including an increased risk of endophthalmitis and other infections, uveitis, and demyelinating conditions.7 Other systemic side effects include an increased risk of infections and aplastic anemia. Thus, close monitoring of patients for iatrogenic comorbidities is necessary.

Additionally, patient education, psychologic counseling, lifestyle modifications (e.g., smoking cessation, limited alcohol consumption, improved dietary habits, exercise), and support play vital roles in improving patients’ quality of life.

Knowledge and vigilance

Autoimmune disorders and their ocular complications pose challenges for eye care and other health care providers. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that these challenges are even greater for patients, their caregivers, family members, and loved ones. Proper management, whether through direct care or referral to appropriate providers and agencies, can be highly rewarding.

Optometrists, being the first line of health care providers, often encounter patients seeking help for ocular manifestations of autoimmune diseases. Therefore, having knowledge of and vigilance for these conditions are essential. OM

REFERENCES

- Smith DA, Germolec DR. Introduction to immunology and autoimmunity. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107 Suppl 5(Suppl 5):661-665. doi:10.1289/ehp.99107s5661.

- MedlinePlus. Autoimmune disorders. National Library of Medicine. Updated April 24, 2021. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000816.htm .

- Rosenblum MD, Remedios KA, Abbas AK. Mechanisms of human autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(6):2228-2233. doi:10.1172/JCI78088.

- El Ameen A, Herbort CP. Comparison of Retinal and Choroidal Involvement in Sarcoidosis-related Chorioretinitis Using Fluorescein and Indocyanine Green Angiography. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2018;13(4):426-432. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_201_17.

- Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TY, Melles RB, Mieler WF; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (2016 revision). Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1386-1394. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.058

- Daruich A, Matet A, Dirani A, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy: recent findings and new physiopathology hypothesis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;48:82-118. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.05.003

- M Castillejo Becerra C, Ding Y, Kenol B, et al. Ocular side effects of antirheumatic medications: a qualitative review. BMJ Open Ophthalmology. 2020;5:e000331. doi:10.1136/bmjophth-2019-000331.