It depends on when it makes an obvious appearance

There is an ever-growing list of things to address with our patients at their annual exam. We are often faced with limited time to examine, discuss and chart, all with the stress of impatiently waiting patients. This forces us to make a decision. There are two camps when it comes to acting on dry eye disease (DED): (1) Diagnose and treat at the time DED is seen during the annual exam, or (2) have the patient return for a separate DED evaluation. Is one camp better than the other? In short, I would argue “no” because there are too many variables.

To illustrate my point, here, I provide two example patient scenarios:

DIABETIC PATIENT

Jane, a 63-year-old female presents for her annual diabetic eye exam. During the exam, she notes that she has been using OTC artificial tears q.i.d. for the last three months with no improvement in vision fluctuation or ocular irritation.

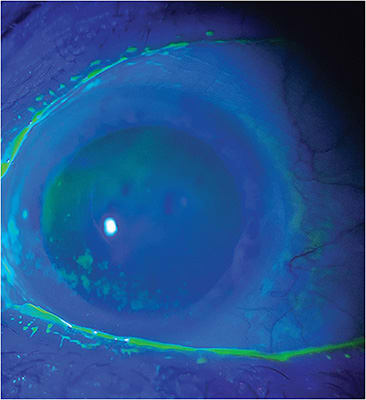

On slit lamp exam, mild blepharitis, grade 2+ meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), and trace corneal staining is noted. Additionally, meibography shows moderate gland atrophy.

During the dilated fundus exam, it is also noted that Jane has mild, non-prolific diabetic retinopathy, as well as grade 2+ nuclear sclerosis, minimally affecting her vision.

While there are quite a few things about which to touch base with Jane, I focus first on what she is there for and is most important: her diabetic retinopathy, Then, since she has mentioned vision fluctuation and the use of OTC artificial tears sans relief, I turn my attention to these findings:

“Jane, part of the reason you are having little success with artificial tears and your vision keeps fluctuating is because the glands in your eyelids are functioning poorly. These glands release oil that keeps the tears from evaporating, and carry many important nutrients for the function of the front surface of your eye. To help these glands start functioning better, I’m prescribing a heat mask, lid hygiene, and ocular nutraceuticals. Consider this your long-term homework, like brushing your teeth. Then, I will see you back in four-to-six weeks to determine whether further treatment is necessary.”

CONTACT LENS PATIENT

John, a 35-year-old male contact lens wearer presents as a new patient for a complete exam and contact lens prescription. He notes mild contact lens discomfort toward the end of the month and fluctuation in his vision when blinking.

Slit lamp exam reveals grade 3+ blepharitis debris, grade 2+ Demodex collarettes, grade 1+ MGD, with difficult gland expression, and decreased tear break-up time. All other findings are unremarkable.

As John’s issue with his contact lenses may be completely related to his Demodex blepharitis and MGD, these findings are the most important part of his exam, so I discuss them and begin treatment.

“John, we naturally have bacteria on our skin, but you have an overgrowth of bacteria and mites, both of which are adding to the poor expression of the oil glands in your eyelids. This oil is very important to keeping your tears from evaporating too quickly. Poor tear quality is part of why your vision is fluctuating and your contact lenses are uncomfortable. To get this under control, I’m prescribing lid hygiene using tea tree oil and a heat mask. Then, I’d like you to return to the practice in two weeks for an in-office procedure to remove any remaining bacteria and mites from your eyelids. Once we get these bacteria and the mites under control, we can properly re-assess your contact lenses and refit you in a different material if needed.”

FLEXIBILITY IS KEY

Many times the choice between the two camps mentioned above is dependent on the type of practice, the patient’s insurance, the busyness of the day, and most, importantly, the individual patient. Thus, flexibility during a non-DED-related visit is key. We must be ready to pivot and adjust because, in the end, the focus is helping the patient. OM