Diabetes related-retinal disease (DRD) has long been considered a microvascular disorder, however as the term now reflects, the entire retina is involved.1 Growing evidence shows that diabetes affects the outer retina (the photoreceptor layers through to the choroid).2-3 As a result, this article identifies these changes and how, specifically, to detect them and, thus, the presence of DRD.

IDENTIFYING CHANGES

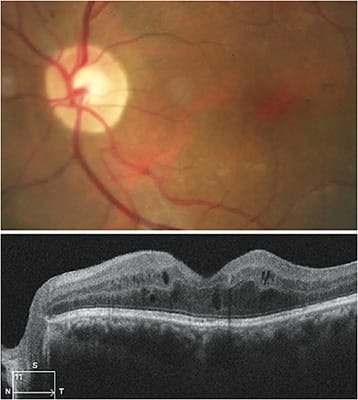

The outer retina, comprised of the external limiting membrane (ELM), photoreceptor ellipsoid zone (EZ) (the junction between the inner and outer segment), retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and choroid plays an important role in the development of DRD, and may indicate early complications before the development of overt DR.4-5

Outer retina layer changes include photoreceptor damage. These changes are thought to be represented by disruption of the ELM or the EZ.

Disorganization of the retinal inner layers is associated with structural disruption in the outer retina, specifically in the EZ and the ELM.6

Hyperreflective intraretinal foci are believed to be lipid-laden macrophages (precursors of hard exudates) or degenerated photoreceptors and RPE hyperplasia.7

Diabetic choroidopathy, due to disruption of the choroidal circulation, the choriocapillaris and choroid vessels in patients who have diabetes, may trigger the development of diabetic retinopathy.8

Changes in choroidal thickness associated with DR may contribute to hypoxia of retinal tissues, resultant impairment of the outer blood retinal barrier, development of diabetic macular edema (DME), and further progression thereof to DME.9

DETECTING CHANGES

OCT provides the delineation of subtle structural changes, particularly in the outer retina and choroidal layers. The assessment of the integrity of the photoreceptor can be made by evaluating the EZ reflectivity. The presence of disorganization of the retinal layers is associated with the disruption of ELM and EZ layers. Hyperreflective foci in the retina and choroid are considered an indication of disease progression, or development of DME. Measurement of retinal thickening can be an indication of DME, and cysts in the outer retina have been associated with having poor visual acuity.9

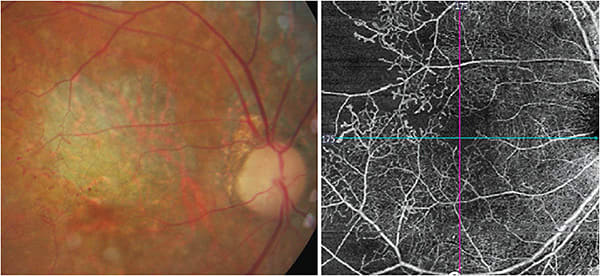

OCT-angiography (OCTA) has aided in the detection of early distinct changes in the retinal and choroidal vascular retinal plexuses in eyes that have diabetes, even without clinically detectable DRD. Specifically, OCTA can reveal vascular anomalies (vascular loops, tortuosity, and dilations of the vessels), subclinical microaneurysms, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, and superficial neovascularization.

Additionally, the imaging technology can show diabetic choroidopathy, including areas of capillary nonperfusion, impairment of the choriocapillaris flow, and enlargement of the foveal avascular zone (FAZ) in diabetic macular ischemia (DMI).

Abnormalities in the structure or perfusion of the FAZ not only result in vision impairment, but a poor prognosis because the condition cannot be treated. DMI should be ruled out in patients who have poor vision at presentation or despite attempted treatment for DME.

Recently, enhanced-depth imaging optical coherence tomography (EDI-OCT) allows for measurement of the choroidal thickness. In diabetic eyes, there is an overall thinning of the choroid on EDI-OCT. A decreased choroidal thickness may lead to tissue hypoxia and, consequently, increase the level of vascular endothelial growth factor, resulting in the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and development of macular edema.10-11

Early deficits in photoreceptor function may precede, or even predict, microvascular damage in the diabetic retina. Electroretinogram (mfERG) can aid in detecting these abnormalities.

CALL TO ACTION

Optometrists should closely monitor patients who have early outer retinal layer and choroidal changes associated with diabetes with three- to six-month follow-up visits, and repeat of imaging.

Those patients who have severe nonproliferative, proliferative DR, and DME should be co-managed with a retinal specialist. Additionally, the OD should communicate all ocular findings with the patient’s health care team. This way, the patient’s other doctors can determine any additional management steps, such as a change in medication.

DRD affects all layers of the retina. While the detrimental effect of DRD is mostly due to impairment in function of the inner retina, the outer retina and choroid may undergo early alterations that impact the prognosis and severity of the disease. Therefore, education, identification, and management of early sight-threatening complications in the outer retina and choroid are imperative. OM

REFERENCES

- A Practical Guide to Diabetes-Related Eye Care. Compendia. 2022, Vol.2022, 1-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.2337/db20223

- Parravano, M., Ziccardi, L., Borrelli, E. et al. Outer retina dysfunction and choriocapillaris impairment in type 1 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2021; 11:15183. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94580-z

- Becker S, Carroll LS, and Vinberg F. Diabetic photoreceptors: Mechanisms underlying changes in structure and function. Visual Neuroscience. 2020:37:E008. doi: 10.1017/S0952523820000097

- Tonade D, Kern TS. Photoreceptor cells and RPE contribute to the development of diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021;83:100919. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100919.

- Borrelli, E., Palmieri, M., Viggiano, P., Ferro, G. & Mastropasqua, R. Photoreceptor damage in diabetic choroidopathy. Retina. 2020;40:1062–1069. doi: 10.1097/iae.0000000000002538 (2020

- Das R, Spence G, Hogg RE, Stevenson M, Chakravarthy U. Disorganization of inner retina and outer retinal morphology in diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(2):202-208. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.6256.

- Uji, T. Murakami, K. Nishijima et al. Association between hyperreflective foci in the outer retina, status of photoreceptor layer, and visual acuity in diabetic macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(4):710-7, 717.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.041.

- Sidorczuk, P, Obuchowsk I, Konopinska, J, Dmuchowska, DA. Correlation between Choroidal Vascularity Index and Outer Retina in Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. J Clin Med. 2022;11(13):3882. doi: 10.3390/jcm11133882.

- Kung EWT, Chan VTT, Tang Z, Yang D, Sun Z, Wang YM, Chan CH, Kwan MCH, Shi J, Cheung CY. Alterations in the Choroidal Sublayers in Relationship to Severity and Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Swept-Source OCT Study. Ophthalmol Sci. 2022;(2):100130. doi: 10.1016/j.xops.2022.100130. PMID: 36249687; PMCID: PMC9560641.

- Querques, G, Lattanzio, R.; Querques, L, et al. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography in type 2 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(10):6017-24. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9692.

- Papay JA, Elsner AE (2021) Quantifying frequency content in cross-sectional retinal scans of diabetics vs. controls. PLoS ONE 16(6): e0253091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253091