With much of the country grappling with extreme heat this summer, there’s a possibility you’ve seen more cases of herpetic epithelial keratitis (HEK). The reason: Heat stress has been implicated as a cause of the herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Keratitis is the most common ocular HSV manifestation. Specifically, HSV keratitis represents a significant global health burden, with an estimated annual incidence of 1.5 million cases worldwide, of which approximately 40,000 cases result in severe visual impairment or blindness.1 Among HSV-associated keratitis, herpetic epithelial keratitis (HEK) is the most common subtype. Loss of corneal sensation and a diminishment of the normal blink reflex (which may eventually lead to neurotrophic keratopathy)2 can result. Additionally, while some dendritic ulcers heal spontaneously without treatment, sequelae can include corneal scarring, thinning, and perforation, as well as secondary glaucoma and macular edema.3 Given these possible outcomes, it’s essential optometrists diagnose and manage HEK.

Diagnosing HEK

Clinicians should obtain a detailed case history, probing for previous ocular and oral infections, recent stressors, and corticosteroid use, as all are associated with the development of HEK.

HEK should be considered immediately if a patient presents with acute, unilateral onset of eye pain, blurred vision, photophobia, and watery discharge.3 A thorough assessment of symptoms can provide insights into the progression of the disease, with dendritic ulcers becoming more visible as the disease progresses.

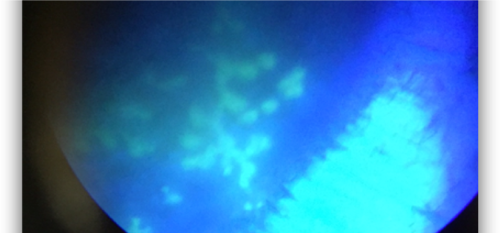

In suspected cases, a comprehensive clinical evaluation of the ocular surface, including slit-lamp examination and corneal fluorescein staining, is typically sufficient to diagnose HEK.3

Additionally, the cotton wisp test can be used to diagnose HEK, as HSV infection can lead to decreased corneal sensitivity (as illustrated above). Specifically, the effected eye will typically show reduced sensitivity compared to the non-infected eye.

While clinical evaluation is usually adequate, laboratory tests can provide confirmatory evidence of HSV infection, if necessary. These tools are particularly valuable for preventing misdiagnosis, as HEK may sometimes be misclassified as keratitis stemming from another source, such as the varicella zoster virus.4,5 Specifically, techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or viral culture can determine the specific viral type involved.6,7

Treating HEK

Treatment of HEK primarily involves antiviral medications that inhibit viral DNA replication.3 The treatment approach depends on the severity of the presentation and the patient’s individual risk factors for HEK (e.g., autoimmune conditions, immunocompromised patients, and a history of previous HSV.)

• Mild-to-moderate cases. Mild HEK typically presents with less corneal involvement. Moderate cases present with more corneal staining/keratitis and possible iritis. To treat these patients, I typically start with a topical antiviral (e.g., acyclovir 3% ointment, trifluridine ophthalmic solution or ganciclovir 0.15% gel) as they are typically sufficient to disrupt the viral infection. In fact, the vast majority of mild cases treated with topical antivirals resolve within 2 weeks.3

• Severe cases. For patients who have a history of recurrent episodes, those who are immunocompromised, or those who present with more severe involvement, I consider adding an oral antiviral (e.g., acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir) and the placement of an amniotic membrane to minimize scar formation and preserve visual outcomes. In fact, for patients who have extensive epithelial damage or a high risk of scar formation, an amniotic membrane can promote wound healing and corneal nerve regeneration, as well as reduce inflammation and vascularization.8,9 It also acts as a physical barrier, protecting the wound from mechanical trauma.

Patient education needed

I recently treated a young woman who had bilateral HEK, including lid involvement and bilateral diffuse geographic corneal ulcers. Two years later, she presented to urgent care and was prescribed antibiotics, which did nothing to help her. As this case highlights, we have to let our patients know about the likelihood of recurrence and instruct them to see an eye care practitioner if they experience symptoms.

Indeed, because HSV is so widespread, many of our patients are at risk of primary or recurrent ocular infection, so promoting awareness of risk factors and symptoms can empower patients to play an active role in managing their condition. A proactive approach to patient education can help mitigate the likelihood and severity of future recurrences.

References

- Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(5):448-462. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.005.

- Lobo AM, Agelidis AM, Shukla D. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex keratitis: the host cell response and ocular surface sequelae to infection and inflammation. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(1):40-49. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.10.002.

- Ahmad B, Gurnani B, Patel BC. Herpes simplex keratitis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed June 25, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545278/

- Milligan AL, Hoffman JJ, Neo YN, Koay SY. Improving polymerase chain reaction diagnostic rates for herpes simplex keratitis: results of a pilot study. Digit J Ophthalmol DJO. 2024;30(1):1-4. doi: 10.5693/djo.01.2024.01.002.

- Hirota A, Shoji J, Inada N, Adachi R, Tonozuka Y, Yamagami S. Rapid detection and diagnosis of herpetic keratitis using quantitative microfluidic polymerase chain reaction system for herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus DNA: a case series. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023;23(1):177. doi: 10.1186/s12886-023-02938-w.

- Madhavan HN, Priya K, Anand AR, Therese KL. Detection of herpes simplex virus (HSV) genome using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in clinical samples comparison of PCR with standard laboratory methods for the detection of HSV. J Clin Virol. 1999;14(2):145-151. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(99)00047-5.

- Nozawa C, Hattori LY, Galhardi LCF, et al. Herpes simplex virus: isolation, cytopathological characterization and antiviral sensitivity. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(3):448-452. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142574.

- Mead OG, Tighe S, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation for managing dry eye and neurotrophic keratitis. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2020;10(1):13-21. doi: 10.4103/tjo.tjo_5_20.

- Elkhenany H, El-Derby A, Abd Elkodous MA, Salah RA, Lotfy A, El-Badri N. Applications of the amniotic membrane in tissue engineering and regeneration: the hundred-year challenge. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02684-0