Delayed recognition of neurotrophic keratitis (NK) can lead to persistent epithelial defects, stromal melt, secondary infection, scarring, and vision loss1; therefore, it is vital to catch NK as early as possible. This article will address the stages of NK, the current interventions related to each stage, follow-up schedules based on interventions, and signs of recovery.

Stages of Neurotrophic Keratitis

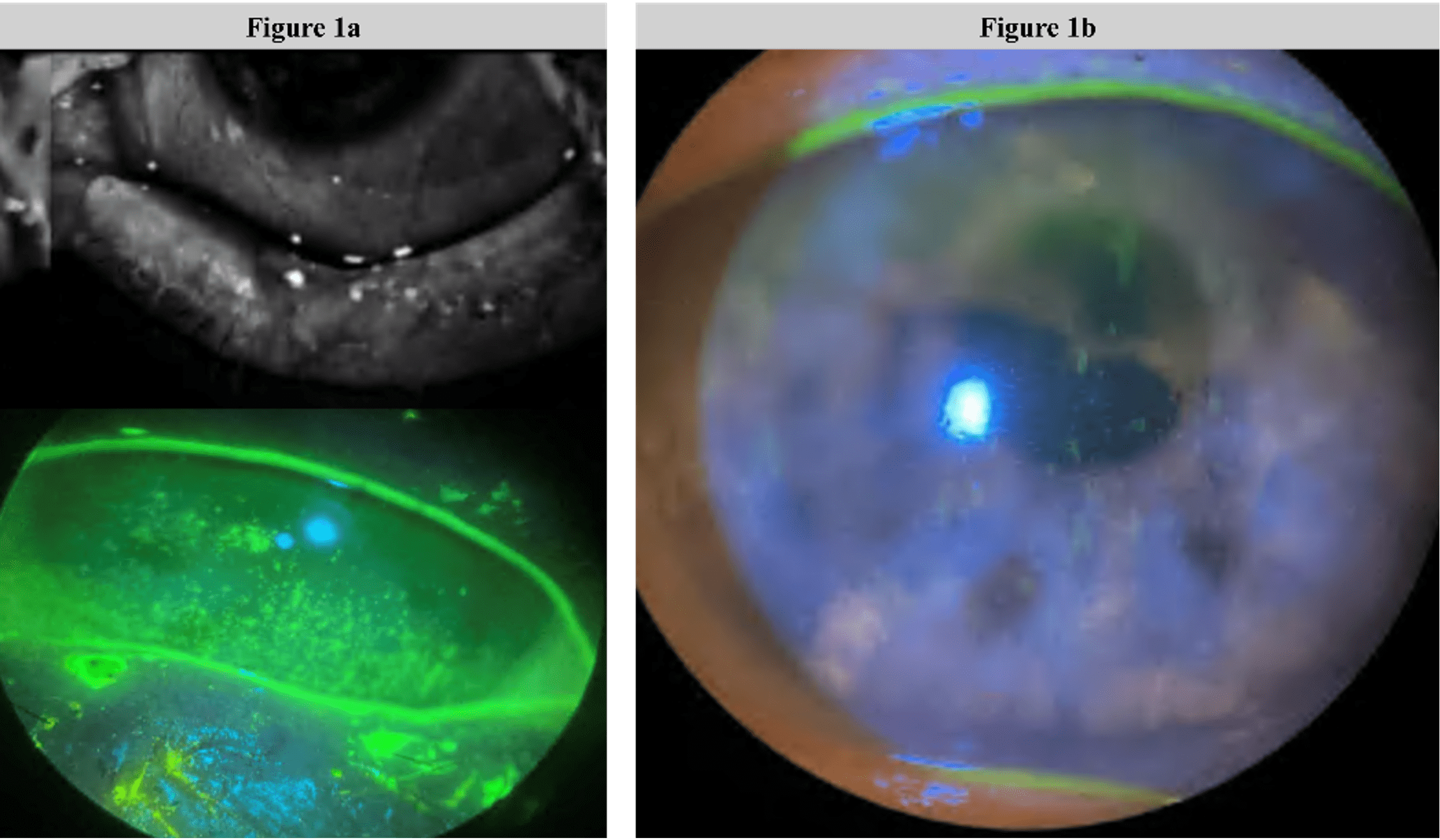

The formal staging of NK via slit lamp exam is a crucial step in formulating a practical plan for intervention, and I build corneal sensitivity testing via esthesiometry into the first visit for patients who have signs of ocular surface disease. It is important to test corneal sensitivity in each quadrant because NK can present with various levels of anesthesia or hypoesthesia regionally. The eyelids should be examined as well because lagophthalmos may result in exposure keratitis that contributes to NK, and vital stains and the Schirmer test can be used to evaluate the integrity of the ocular surface and tear film. To ensure the correct diagnosis, additional examinations such as in vivo confocal microscopy and fundus exam can be performed.2 The 3 metrics that are most important for guiding my decisions in NK are (1) corneal epithelial condition at the slit lamp (staining pattern and objective photography); (2) tear film homeostasis via point‑of‑care metrics such as osmolarity and MMP‑9; and (3) corneal sensitivity over time with either a Cochet‑Bonnet or a simple wisp test.

The disease severity of NK is classified into 3 stages according to the level of corneal damage using the Mackie classification. Stage 1 NK appears as a persistent epitheliopathy that does not behave like straightforward dry eye disease (ie, symptoms are absent or substantially less than would be expected). Patients may present with a dry and cloudy epithelium, corneal edema, and superficial punctate keratopathy. In stage 2, patients experience persistent or recurrent epithelial defects, which usually have a circular or oval shape and are usually found in the top half of the cornea. Stage 3 is characterized by corneal ulceration involving the stroma, which can result in stromal melting and corneal perforation. After diagnosis, these stages can be used to guide treatment selection.1

Current Interventions

When counseling my NK patients, I always frame the condition as chronic and advise them that optimal healing may require multiple staged interventions. I find that this is an important step to getting their buy-in for the treatment course that may lie ahead.

Stage 1

Preservative‑free lubrication—drops by day and ointment at night—protects the epithelium and reduces friction during blinking. An immunomodulator is an option, or optometrists may cautiously add a topical corticosteroid and monitor closely to control surface inflammation.3 For a low tear meniscus once the ocular surface inflammation is controlled, I consider punctal occlusion to retain the tear reservoir.4 Collagen or silicone plugs and cross‑linked hyaluronic acid canalicular gel are all possible options.5,6 I use cross‑linked hyaluronic acid canalicular gel in patients who have trouble tolerating the flange of a conventional punctal plug or who previously had punctal plugs dislocate. A topical antibiotic may also be prescribed until epithelial closure if a persistent epithelial defect persists or there is an increased risk of microbial infection, either from exposure or if a patient is immunocompromised.

When herpes is a contributing cause, whether herpes simplex virus (HSV) or varicella zoster virus (VZV), I initiate oral or topical antivirals; in recurrent HSV disease, long‑term oral prophylaxis may also be warranted. I typically have my patients continue valacyclovir 1g by mouth daily, especially in the setting of multiple recurrence.7

A bandage contact lens may also be used along with other therapies to shield the defect, although this requires close follow‑up to monitor for hypoxia or microbial risk. Also, in stage 1 epitheliopathy, scleral lenses can be helpful to protect and hydrate the corneal surface.8 Recombinant human nerve growth factor (rhNGF) or cryopreserved amniotic membrane (CAM) can also be considered in stage 1 patients who are nonresponsive to the above therapies.9

Stage 2

Cenegermin (rhNGF) is FDA approved for stage 2 to 3 NK to support corneal nerve recovery.10,11 Cryopreserved amniotic membrane can also be placed with or without a self‑retained ring under a collagen shield due to its anti‑inflammatory and antifibrotic effects that support re‑epithelialization.12In a patient with NK and 2 or more punctate epithelial keratopathy, I usually place the CAM that day and initiate topical medications, as discussed above. Using a combination of a taped upper lid and a collagen shield when placing the CAM can not only help keep the membrane stable and centered, but also improve patient comfort.

Stage 3

When managing patients with stage 3 NK, I recommend using a sutured CAM or a temporary or permanent tarsorrhaphy to reduce ocular surface exposure and close nonhealing defects, depending on the condition of the ocular surface and the extent of the exposure. If there is a perforation, I apply a cyanoacrylate adhesive with a bandage lens and consult with my corneal surgeon because these patients may need further surgical intervention. If there is a descemetocele formation, these patients also need careful monitoring to prevent perforation. In more severe cases, I may also consider corneal neurotization to restore the potential for innervation. This procedure is more rarely utilized, but has been successful in some of our pediatric cases.11,13

NK: What I Look For

Neurotrophic keratitis often hides in plain sight, so when I get an ocular surface disease referral or I see a postoperative patient who is not improving as expected, testing corneal sensitivity is always a first step in determining whether I am dealing with NK or conditions that may present in a similar way, such as exposure keratopathy, severe dry eye disease (DED), persistent corneal infections, and neurotrophic-related postsurgical complications. It is also important to keep in mind that severe DED is likely to lead to NK if not treated comprehensively.

If a patient has an epithelium that looks painful yet provokes little discomfort—especially after the failure of routine anti‑inflammatory and lubrication measures—that is a definite signal that the patient may have NK. This may be especially true if the patient has another condition that is a common risk factor for NK, such as diabetes or prior herpetic disease, trigeminal ablation, or history of multiple ocular surgeries.

Follow-Up Schedule

I schedule follow‑up appointments based on the disease severity. Generally, I shorten the follow-up interval during active epithelial disease, then extend it once the ocular surface stabilizes.

A healthy patient with an initial mild epitheliopathy, for example, could be seen every 3 to 4 months once the condition is stable. However, in patients who have a history of multiple ocular surgeries, previous infection, or a higher risk of NK recurrence, I may have them return every 1 to 2 months. If a defect stalls or ocular surface exposure is high, I escalate treatment and engage with my surgical colleagues to determine if there is an apparent structural risk to the cornea (eg, progressive thinning or risk of perforation). I also will not hesitate to repeat CAM placement in addition to cenegermin and, if progress stalls, I collaborate with my corneal surgeon to escalate to temporary tarsorrhaphy or a sewn‑in, thicker CAM.

Signs of Recovery

Improvements in corneal nerve density, morphology, and sensitivity, in addition to tear metrics, are signs of true recovery, rather than transient epithelial closure. These improvements in corneal nerves can be monitored using confocal microscopy. Overall, what we really want to accomplish in these patients is a sealed, stable epithelium, restoration of physiologic corneal nerve, corneal epithelial cell function, and a healthier tear film.3

References

-

Gurnani B, Feroze KB, Patel BC. Neurotrophic Keratitis. [Updated 2025 Mar 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431106/

-

Sacchetti M, Lambiase A. Diagnosis and management of neurotrophic keratitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:571-579. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S45921

-

Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):575-628. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.006

-

Chen F, Shen M, Chen W, et al. Tear meniscus volume in dry eye after punctal occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(4):1965-9. doi:10.1167/iovs.09-4349

-

Dursun D, Ertan A, Bilezikci B, Akova YA, Pelit A. Ocular surface changes in keratoconjunctivitis sicca with silicone punctum plug occlusion. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26:263-269.

-

Packer M, Lindstrom R, Thompson V, et al. Effectiveness and safety of a novel crosslinked hyaluronate canalicular gel occlusive device for dry eye. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2024;50(10):1051-1057.

-

Burling L. Key cornea trials: the legacy of HEDS, the promise of ZEDS. EyeNet. 2021. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/key-cornea-trials-legacy-of-heds-promise-of-zeds

-

Frogozo M. Scleral lens for persistent epithelial defect in neurotrophic keratopathy. Contact Lens Update. 2022. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://contactlensupdate.com/2022/04/28/use-of-a-scleral-contact-lens-to-manage-a-patient-with-a-persistent-epithelial-defect-due-to-neurotrophic-keratitis/

-

Cunha A, Buunya V, Woodward M, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. American Academy of Ophthalmology EyeWiki. Updated August 18, 2024. Accessed December 18, 2025. https://eyewiki.org/Neurotrophic_Keratitis

-

Oxervate. Prescribing Information. Dompé US Inc. December 2024.

-

Mukamal R. Neurotrophic keratitis: two treatments in practice. November 1 2023. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/neurotrophic-keratitis-two-treatments-in-practice

-

Brocks D, Mead OG, Tighe S, Tseng SCG. Self-retained cryopreserved amniotic membrane for the management of corneal ulcers. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:1437-1443. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S253750.

-

Dana R, Farid M, Gupta PK, et al. Expert consensus on the identification, diagnosis, and treatment of neurotrophic keratopathy. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21(1):327. doi:10.1186/s12886-021-02092-1.